YOU CAN TAKE A BABY TO SCOTLAND: An Excerpt from Ayun Halliday’s NO TOUCH MONKEY!

I’ve gushed on about Ayun Halliday in these pages before. She is one of MUTHA’s mother/writer idols. So, hey—guess what? Feminist publisher Seal Press has just reissued Halliday’s super-hilarious, best-selling memoir, No Touch Monkey!: And Other Travel Lessons Learned Too Late. Stephen Colbert said that these tales of (pre-Internet!) global adventures made him “laugh hard on nearly every page.” (And then maybe on the others, he wept?)

As Ayun tells it, in a new intro to the new edition, No Touch Monkey is “a record of what it was like to be young, foolish, curious, unfettered, stupid, hungry, untethered, amazed—and offline.” Here’s a bit to sample, excerpted from right after her baby, Inky, was born—and then latched on, wrapped up, and strapped in for the ride….

P.S. If you want to read the rest, you can get the book at your local indie. (Go get all her books! And zines!) – Meg Lemke

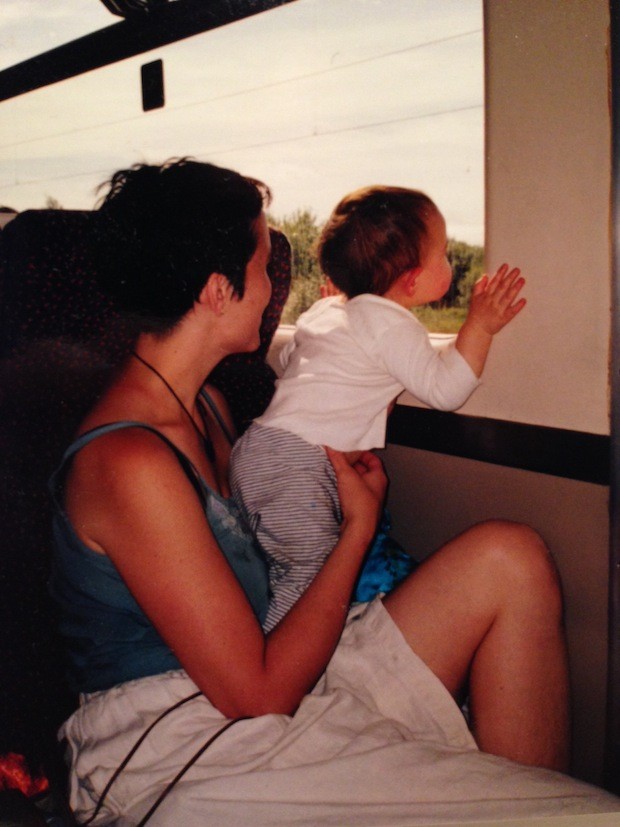

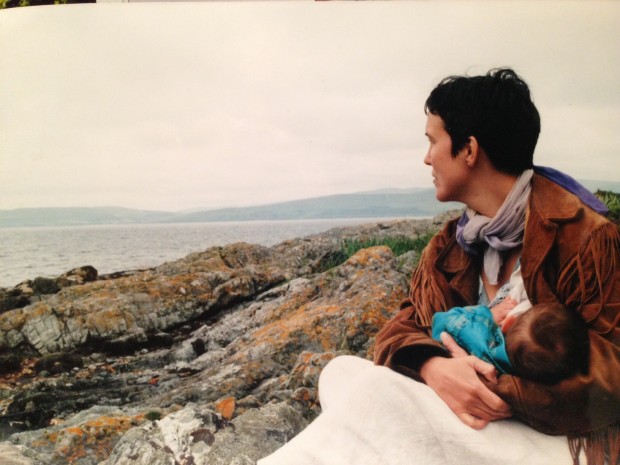

EVI has been published since Ayun’s kid Inky was teeny–and now she’s in college!

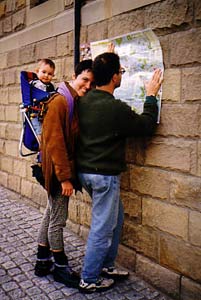

Ayun and Inky in Scotland

Just shy of one, Inky was a seasoned domestic shoestring-traveler. At four weeks, she lived in a tent on Bread and Puppet Theater’s farm in rural Vermont. Overriding Greg’s objections to the strong August sun on her virgin skin, I carried her into the ring for her Domestic Resurrection Circus debut before she could hold her head up. There were obligatory visits to the grandparents in Cape Cod and Indiana. We spent two months in Chicago, acting in one of Greg’s plays and crashing with various friends, enlisting many others as unpaid baby sitters. Incorporating a baby into these adventures was not without stress, but I figured it beat sitting around a miniscule tenement apartment, wondering what stay-at-home mothers did to fill their long days.

So when our good friend Karen announced that she would wed her Scottish beau toward the end of a performance workshop her company taught every summer at Glasgow’s Centre for Contemporary Art (CCA), there was no question that we would go, especially since it meant Inky would get one chance to wear the fancy velvet dress her grandmother had purchased at Bergdorf Goodman before she grew out of it. When contrasted with the fetid skank of July in lower Manhattan, Scotland’s cool summers seemed a wonderfully wholesome climate for hauling around a small child. Other small memories of my first unchaperoned trip abroad crowded aside sexier recollections from more exotic locales. I trailed Greg around our 340-square-foot apartment, regaling him with descriptions of mossy tombstones, a kilted street performer wielding hand puppets on his feet, and the rhubarb-and-custard boiled sweets I bought from a young Pakistani confectioner who complimented me on my Hoosier accent in a brogue thicker than Braveheart’s. For English speakers traveling with a baby, I could think of no destination more hospitable than Scotland. Financially, it was a reckless proposition, but then inspiration dawned. If Greg and I both enrolled in the performance workshop, we could deduct the whole trip from our taxes! When we called Karen to tell her of the scheme, she invited us to stay with her and her fiancé, CJ, in his flat’s extra room. Perfect! Our only expenses would be food and two plane tickets, since children under the age of two flew free as “lap passengers.” I immediately rushed out to have Inky’s passport picture taken and buy art supplies, figuring if the groom was nice enough to open his home to three strangers, one of them incontinent, for an entire month, our wedding present should be creative and laborious rather than nice and registered for.

After discussing our plan with her fellow company members, Karen called to tell us that Greg would pay full tuition, while I audited, since they anticipated there would be times when caring for Inky would preclude my participation. The terms sounded good to me, especially since Karen’s co-teachers probably assumed I’d need a private place to breastfeed. Hell no! I didn’t care who saw. Besides, her bumblebee rattle and a baggie full of Cheerios would keep her entertained while her mother and father immersed themselves in the kind of vibrant artistic community

it’s difficult to find in the States, particularly at the bargain-basement rate of one hundred twenty-five pounds for three weeks. The morning of orientation, we bolted our breakfast and hurried to the CCA, a gallery and theater complex located right on the main shopping drag. Snooping around its bookstore the day after we arrived, I’d watched conservatively dressed families push through the glass doors, expecting them to turn tail immediately upon realizing they’d blundered into a hornet’s nest of avant-garde art. Instead, they spent twenty minutes reviewing incomprehensible film loops and a series of photographs by the director John Waters, before wandering back out. Never before in my experience had the art snobs and the bovine mainstream intermingled so promiscuously. Next to childbirth, this was going to be the most amazing experience of my life!

It was our fourth day in Glasgow, and while I had not grown used to the cold rain or the skies that stayed light until 11 p.m., we were over jet lag and I was eager to commence with our justification for imposing on CJ’s hospitality for such a long stay. He remained unfailingly gracious, as baby food jars crowded his cabinets, disposable diapers befouled his meticulously kept trash bin and small, sticky hands groped toward his alphabetized CD collection, but I couldn’t help thinking that, in his shoes, I’d prefer to wander around the apartment naked, farting, and bathing whenever I wanted. Not only would the workshop give structure to our visit, it would introduce us to a whole new set of people, who would give our hosts a break by taking us out to pubs and dinner. I studied the others, wondering who would emerge as our close friends. The tiny German with cat’s eye glasses and a flowered schmata looked cool. “Who’s this, then?” a sharp-faced Englishwoman leafing through the orientation materials at the next table asked. In the subservient manner of new parents, we introduced Inky first, then ourselves. “Aren’t you sweet,” she cooed, as Inky hammered a spoon against my coffee cup. “You and Mummy wanted to see what Daddy would be doing for the next three weeks!”

I was shocked at how quickly her innocent mistake proved prophetic. After we had gone around in a circle, submitting brief bios of name, nationality, and performance background, we located to a black box theater, where we were told to find partners for the first exercise. Greg nodded at a Mohawked young Scotsman in Doc Martens and a ragged, sleeveless T-shirt. As other pairs headed for the stage, my preordained partner yanked my shirt to the clavicles, eager to wash down her Cheerios with milk hot from the cow. The others began to explore radical movement, squirming and jumping, Greg and the punk spinning each other like reckless schoolgirls. My partner shat herself in the bleachers. Feeling an uneasy mixture of conspicuous and invisible, I pulled her, protesting, behind an industrial paint bucket to freshen up. Greg and Karen kept glancing my way, aware that I was falling behind the rest of the herd. I waved and smiled, miserable.

Later, when a distinguished speaker took the podium to impart her theory of “performativity,” my partner burped, squawked, and trilled random bars of “Baa Baa Black Sheep.” When the lecture was upstaged by a stuffed bumblebee launched from the audience, its wings-cum-teething-rings hitting the black floor with an impolite thwack, I knew the jig was up. Greg offered to divvy up the baby-minding responsibilities, but between the class’s need for continuity and Inky’s unflagging passion to go to second with Mommy, it wasn’t a workable solution.

It wasn’t long before the other participants forgot that I had started out as one of them, worldly, artistic, eager to make a fool of myself presenting underrehearsed, site-specific assignments in the public gardens. What did they think when I showed up for noon break with Inky and a carefully assembled lunch for Greg—that I was a mousy, clinging wifey who filled the giant void in her existence by making her family her fetish? If only Radhu, Channi, and Lucien, my number-one Romanian fans, had been on hand to tell them about my triumphant history on the international stage. The tedium and disappointment endured in the name of low-budget theater—the maddening aesthetic discussions, the utter indifference of the Aspen power brokers, the frozen, food- free thirtieth birthday in Transylvania—all this seemed downright jaunty when viewed against the tedium and disappointment of early motherhood.

“John’s got a kid, too,” Greg told me one day, nodding to his Mohawked buddy as the workshop participants tumbled into the CCA’s main lobby, twenty minutes later than their official dismissal time. I’d spent those twenty minutes shooing Inky away from the electrical outlets and remembering the glory days when I could combat the boredom of unforeseen delays by reading or writing in my journal. If only I’d known at the time how fortunate I was, waiting at 2 a.m. on an Indian railway platform for a connection running three hours behind schedule.

“You do?” I cried, smiling so broadly I could have fit John’s entire head in my mouth. “That’s great! What’s her name?” With luck, this fellow parent would notice that I was not waving but drowning. A cozy image sprang to mind, Inky and John’s kid happily playing on the floor of his flat, while the adults lounged on battered, second-hand furniture, mugs, or better yet, empirical pint glasses in hand, listening to music and laughing with our heads thrown back. “Please let his female counterpart be as good natured and sociable as he is,” I prayed, crossing my fingers in the hope of finding a confederate in similar straits, who’d make me glad the workshop was barred to me, that’s how much fun we’d have yucking it up in her kitchen when we got sick of roaring around town with our babies.

His reply came encrypted in a thick Glaswegian accent. “Ah th’ weeyuns nut uh gull—zwee boy, loonan blue. Sthree hears zold. Thas huh trip, huh? Doont live wut me, but I teak hum ever dee wi’ ow fay. Weir goo frens, me oon loonan blue.” As best I could figure, the child was a boy, already three years old to John’s disbelief. Although he didn’t live with his father, they were close and John made sure they saw each other every day. Only after it had been spelled twice did I realize that I had heard correctly: John’s son’s name was indeed Loonan Blue. With that, John borrowed twenty pence to call Loonan’s mother, telling us that they both had crazy schedules that wreaked constant havoc on their already precarious child-sharing system. To complicate matters even further, his squat had no phone. “Ha boat looz mah mine train t’ keep tractor ooze gut Loonan,” he complained, tugging his hawk in frustration. My fledgling vision of an invitation to spend the next three weeks loafing on an extended playdate in cozy local digs went up in smoke.

Instead, Inky and I crisscrossed Glasgow’s gray streets in weather ranging from fierce downpour to bone-chilling mist. I was beginning to understand why so many of the traveling parents I’d encountered in Southeast Asia had been British, collecting the dole in absentia while their children frolicked naked on the beach. As a tourist destination, Glasgow had a lot to recommend it, much more than was readily apparent on my first visit ten years earlier. Back then, Nate and I spent a rainy afternoon trudging around Sauchiehall Street with our backpacks on to avoid a left-luggage room fee, eventually repairing to Pizzaland to share the cheapest pie on the menu and about fifteen complimentary sugar packets. Angling the metallic gold umbrella I’d bought in an East Village discount store in such a way that my lower half got drenched but Inky’s eyes were spared the proverbial poking out, I sighed, remembering. The delusion that, with forewarning of the limitations imposed on mothers of small children, I could have made more of my early freedom was as compelling as crying in a mirror. Had I but known, I wouldn’t have been such a penny-pinching slave to convention! My succession of boyfriends and I could have blown our shoe-string budgets on beer and slept in the same dumpsters that yielded our surprisingly well-balanced meals! It would have been a gas, like the first half of Trainspotting, before all those overdoses cast a major pall over Iggy Pop and that sleeveless, sequined party dress. “Git uh grrrrip on yur sef, gull,” I admonished myself aloud, figuring it didn’t matter if anyone overheard me practicing a Glaswegian accent. Mine was the mangled burr of an imposter, but at least I wouldn’t appear to be engaged in a lunatic’s public monologue, not with the little pitcher on my back. My sturdy inner Scot was right: Moping around wasn’t going to salvage the situation. If I had to undergo existential, maternal angst, at least I was doing so in a city loaded with museums, art galleries and good public transit, where everyone spoke English, sort of.

Excerpted from No Touch Monkey!: And Other Travel Lessons Learned Too Late by Ayun Halliday. Available from Seal Press, a member of The Perseus Books Group. Copyright © 2015.