How Fierce Intensities Can Linger Within Us: A Conversation with Carey Salerno

I had the pleasure of hearing Carey Salerno read from The Hungriest Stars at the Rhymer’s Club in the East Village, and I was immediately intrigued. The poems touch on grief, fertility loss, pleasure, and the imagination in ways that—like the gardens that appear across the poems—offer enchanting pathways into memory and reclamation. When you flip through the book, you’ll see constellations and visual poems that the poet created from her own medical reports. And the poems themselves rebel against the right margin, showing us what more looks like as language cascades across and then down the page. As someone who has dealt with miscarriage and health issues, I found myself transfixed by the poems’ layering of image and story to explore loss, pain, and beauty. I’m so grateful to Carey Salerno for this conversation. My questions arose from the excitement of reading this beautiful and necessary book. – Tyler Mills

TM: I love how The Hungriest Stars situates the “I” in the cosmos, with and in the Gardens of Paradise. The Gardens of Paradise is a spiritual metaphor that in your poems also locates loss within mystery, within the divine and unknowable. In your book, there are sections titled “The Binaries” that are spliced with constellation maps, like Cygnus and Taurus, which add another layer to how we approach these poems. The language is expansive, the lexicon drawing from astronomy, botany, and medicine. When I read these poems, I feel like I am in a densely grown, luscious garden; every sense is piqued, and I feel like the long lines carry me in waves of language sonically interwoven with memory. A cosmic moment I keep coming back to is this one: “As in the elements released on crash contact were mostly metals, were heavy glitter in the solar winds, scattered recklessly, sparkling; impressing the grounds of the bodies of both stars.” What initially drew you to the cosmic imagery that the poems keep returning to? The book’s cover is a mystical hand adorned with rings in relationship with—almost measuring—the moon.

CS: What initially drew me to this imagery was the nature of relationships between objects in the cosmos, that on a grander scale there’s an existence between elements in space that seems so much like that within our earthly ecosystems. The way stars coexist with each other, turn on each other, consume, grow tired, refuse to die, it all feels so immediate and relevant to human existence. And what I like about drawing parallels between the cosmos and human life is that it inherently reflects the grand personal scales within which we operate as singular beings. We are, to many degrees, the centers of our own worlds, which often toggle between feeling very large and very miniscule, significant and trivial. I wanted to iterate and explore the feelings of the sheer magnitude of existence wherever and however it falls on the scale and articulate how we might be easily overwhelmed by its power and endurance, both of which are beyond us and nearly beyond our own comprehension.

I really appreciate that you feel the cover resonates with the poems in this book. Yes, it’s meant to signal excess, desire, and dominance. The poems are absolutely maximalist, so the rings stacked, chunky, multi-colored and adorning unapologetically feel as if they’re in conversation with the long lines and expansive language of this book’s poems. The hand is either reaching for the moon or demonstrating its ability to cover it, which also symbolizes some of the major themes in this collection. Definitely there’s the central conversation about power and personal agency.

I think a lot about sayings like, “she has me in the palm of her hand,” which to some can seem so grandiose and big. It’s okay if the world is only that big, but what these poems reach for something bigger, for harder, intense magnitude, something greater than my physical entity. Personally, I want what stars have, the ability to eat the moon, the ability to give or suck the life out of another star.

In the lines you quoted, which describe the act of a kiss and beyond that the intensity of hungry sex, I wanted to focus on how fierce intensities can linger within us, deepening hunger instead of satiating it. They can awaken hunger within us that we were never familiar with, never knew resided there. The process of learning about these hungers is delightful and surprising. I like to think about how the taste of something might leave us wanting only that one thing forever. I get hooked on and fed by that kind of pleasure.

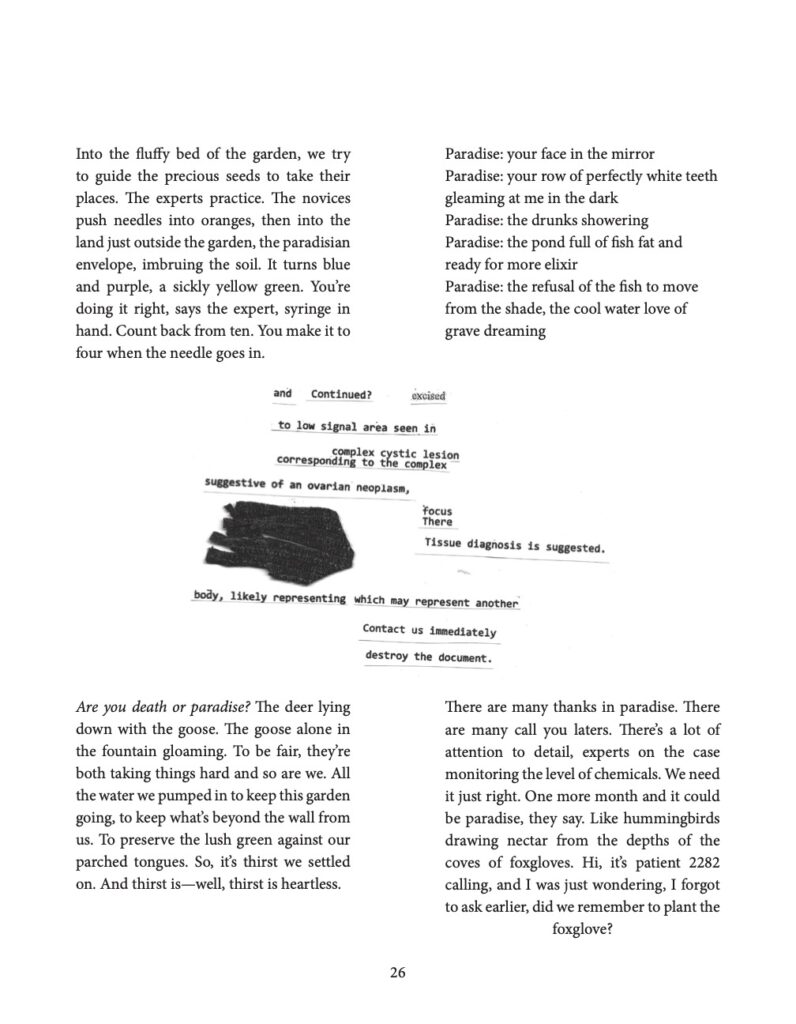

TM: Crocuses, tulips, and orchids transformed by metaphor and made physical through the rich details you give thread through lyric moments like “The Tulips (The Cervix),” where the deer consume the “fleshy tulips / in springtime.” The speaker says, “I wanted what I wanted but what the deer got to first. Like on the operating // table, after slicing into my abdomen, after the frozen sections came back negative, the / surgeon reluctantly followed my orders, taking only what had to be taken” (13-16). I also found myself reading and rereading your poem “Gardens of Paradise (Eden Anamnesis),” a multi paneled, visual poem including medical history notes and lyric language made mythic: “What we manicured. What we cut away. What we forgot to tell each other. What we only told ourselves in our downy beds.” The speaker urges us to contemplate how “Paradise is the secret garden within the obvious garden, the one you plant in the dark when everyone is fast sleeping, the one accessed by skeleton key…” How did you conceptualize the shape of this book (its parts) as you were writing it? How did the mythos of the paradisal gardens emerge?

CS: I once told a friend of mine that I have this thing I call a “pleasure bank,” which is an internal place where I store up all the little pleasures I feel, as if placing them in a box, and I love the feeling of revisiting them when I’m all alone. From inside that box is where I want to meet everyone I know and care about or could care about, but the thing is that it’s a nearly impossible place to get to or to let anyone in. Still, I crave that connection so deeply, knowing how it feeds me so endlessly.

I like thinking about what resides within each of us that induces our deepest pleasures. I’m less interested in the ordinary—what we might say out loud to another person or make some kind of small talk about. I find that all very overcooked and predictable, like I’ve just heard it and said it all before so why even are we talking? Why give energy to a feeling I’ve already well rehearsed, performed, memorized? There’s so much beneath our own surfaces, places we hope to spend all our time if we could, feelings we wish we could feel forever if we could.

Paradise isn’t the thing we look at and call paradise, the thing we spend our time curating and perfecting—what’s visible—it’s the thing below that, the driving force behind the making of paradise that’s actually paradise. I’m also more interested in the creative processes and makings of personal paradise than I am in the public evidence of its existence. If everyone can see it, if it’s obvious, then somehow the resonance of its meaning can be made more shallow. We can allow ourselves to call something beautiful for its surface value without considering its depth and layers, the textures of it.

So, I think the mythos springs from these pathos, the fact I want to live a life where I’m trying to tunnel below the veneer and persist in that act, to find fulfillment in that act. I’m less interested in playing a part I know I can play over and over again, though maybe that also is a kind of paradise? One of predictability, one of comfort?

And the structure of the book follows the lead of these desires, though the structure revealed itself only after most of the poems were written. Most of the poems are rather long, and I knew I needed to try to give the reader some kind of framework to approach them in smaller bits. If there were no sections, the book would be really overwhelming to any reader as it was to me. I wanted the star pairs poems to anchor the book in six sections of six poems, acting as a place to return to while also advancing the narrative throughline, the relationships between the stars deepening and intensifying as the poems progressed. There was a lot of wildness in this book as it came together. I was glad for it to arrive so unapologetically. The structure certainly isn’t trying to compensate for any perceived deficit when it comes to structure but to recognize the need for tension between the wildness of the flower which exists within the confines of where it’s been planted and its plot, its pot, or its little “permanent” patch of ground.

TM: What you said about the creative process and personal makings of paradise really resonates with me. I keep thinking about the privacy of this kind of deep thinking and making, even when we are doing it in community with others. This kind of individuality is so uniquely human—a mind and heart combination AI can never touch. What you said about your book’s structure too, how there was “a lot of wildness” as the book came together, makes me think of a garden. (Full disclosure: I do not have a garden, other than on some windows, but I love and respect people who are serious gardeners.) In The Hungriest Stars, I can imagine sections of a garden, some with wildflowers, where there is the touch of the gardener and then the magical creative force of the thing itself—the creation—that blooms. How did you select the flowers that become focal points in your poems (like the peony in “The Quartet (The Shore, the Peony, the Palm-reader, the Sugar)” and the sweet pea in “Sweat Pea (Mendelian Paradox), for example)? Did you have a kind of personal constraint you were working with (where you chose certain flowers from a particular category of plant) or were these linked to personal experiences and memories? Or a bit of both?

CS: If it’s of any comfort, I have two failed gardens, or perhaps they are only failed by the standards of others or the ones I might have held myself to when I created them. Now they are both wild and whatever was in them dead or alive is living on and doing as it will of its own accord. At first, I was unnerved by what I’d done, but now I see it as a success story for both myself and the plants—we are evidence of survival in a myriad of ways: I with my recovering perfectionism (among other things), the seeded garden evolving naturally without artificial intervention.

The flowers in these poems were those populating my immediate environments, save the poem about the fungal orchid. The peony, god rest its soul, was just outside my front window for years until it was mistaken for a weed and ripped out to the root. I cried after that. The sweet pea are ubiquitous in the countryside in Michigan during the summer, and they’ve always been one of my favorite flowers. They’re so vibrant and even as they appear flimsy, they are resilient. That I could weave them in with musings about Gregor Mendel worked so well. Doing that drew me back to the days I thought I’d be working in medicine, to when I loved studying biology, genetics, invertebrate zoology. I probably still would if I weren’t always reading something else. It was nice to be immersed in that language again.

TM: Wait, did I miss that at one point in your life you were in a pre-med program? Wow! When did you turn to writing? Did you find yourself reflecting on your studies while writing the poems set in medical spaces in your book?

CS: The answer to this question is complex, but the short of it is that, yes, all through middle and high school I was on a med school trajectory. The only colleges and universities I applied to were pre-med focused. In fact, my worst grade in high school (B-) was in 10th grade English class. My favorite subjects were the sciences; anatomy, chemistry, pathology. I really loved that line of study. When I got to college, I took literature classes as a “break” from science and just ended up falling in love with the study of poetry. I had terrific teachers, including poet Herb Scott and my African-American lit studies Prof., Catherine Cucinella, who introduced me to the works of Ralph Ellison, W. E. B. Du Bois, and James Baldwin. After doing the lit-science dance for a while, my passion for creative writing intensified. I officially transferred majors, graduating with an English degree focused on creative writing and a minor in biology. About a month after that, I was gleefully in my MFA program. It was so dramatic, especially for my family, many of whom just couldn’t wrap their minds around it—that’s poetry!

TM: At the core of these poems is grief—diagnosis, illness, surgery—and how these issues can center around fertility. As someone who has gone through multiple pregnancy losses myself (one an ectopic surgery), I felt so seen in these poems, which made this particular pain universal and also conveyed something so personal to the book’s speaker. “Ode to Darnel (Ode to Crocus)” shook me deeply; the poem praises “the early morning charge nurse Darnel who escorted me into the operating theatre / where in my cornflower blue gown and goose-pimpled skin beneath a bleach slubbed cotton // robe I was laid pugnaciously sobbing” (1-3). The poem offers this lonely and painful moment before the body is opened, before something is taken. In the poem, the crocuses remind the speaker of loss (“crocuses and days and days and days and then the year after // in anticipation”) and the way medical workers can bring such grace and care to some of life’s most painful moments: “Darnel, how I loved you for simply squeezing my hand I will never forget it.” If you feel comfortable sharing, what were you thinking about as you drew from these personal experiences and shaping the multilayered poems in this book? What was your process like while working on these poems?

CS: I was thinking about Darnel’s hand, the feeling of his touch, the weight of it steadying me, the sense of his palm and fingers, and how I’d never felt an embrace quite like that in my life. It shocked me as it stabilized me. I’ve held so many hands and certainly my hand has been held countless times for countless reasons, but never in this way, and it was in a way I couldn’t, at first, quite describe, which is what called me into the poem, the desire to pinpoint that feeling which evoked so many feelings all at once.

And it was almost like there was a transmission between our skin, some sort of reassurance he was communicating to me on what was probably a less than two-minute walk. That steadfastness with which he held me is the steadfastness I find so impressive about the crocus. The fact they bloom in winter when the ground is hard and the air is harsh is a marvel to me, and that was the way Darnel seemed, in that moment and to me, to bloom in his position as a nurse, which is a very difficult and emotionally onerous job.

The poems work the couplet, most often, to position two or more narratives or landscapes alongside each other. They aim for sidling, for connection and parallel. These dimensions echo the textures of our own internal landscapes, the tangents our brains get on when we have a thought and suddenly we’re lost in our minds and don’t know how we got there. It’s a beautiful feeling, unique onto ourselves, and difficult to articulate to others, which makes human connection that much more difficult—that we can’t just absorb people into us like amoeba but actually have to articulate what we think and feel, and what comes out is so scaled back, so scant compared to the whole of it. These poems strive for the whole of it (and seemed to protest when I’d try to redirect them otherwise), which is why they are constantly qualifying and requalifying statements, refusing to end, refusing to allow their substances what might be a familiar exit.

The process of writing them was rather infuriating, especially at first when I went to edit the poems and instead of “getting leaner,” they elongated themselves, growing twice, three times, four times their original size and seemed only to be hungry to get bigger. I knew I felt that desire myself, but that expansiveness is poignantly channeled in the structure of these poems. I joke with people that these poems are Brigit Pegeen Kelly coming back to haunt me after I complained about her long lines in The Orchard. I felt that way when writing this book sometimes, like I was getting served some due karma. That’s not to say it was altogether disagreeable. It also felt comforting and apt, as if a conversation I’d started long ago with myself and with poetry was coming back around finally to clarify itself, to teach me what it was that I needed to know and was finally ready to learn.

TM: Growth, hunger, and expansion play out in such richly textured ways in these poems. Looking at them on the page, I feel like I’m in front of enormous oil paintings or infinitely detailed, multi-paneled tapestries. You mentioned Brigit Pegeen Kelly; who else were you reading and thinking about as you were working on the poems in this collection? The Hungriest Stars is your third book—and it’s incredible. I’m so excited about and to keep reading future poems. What would you say to writers who are assembling a book right now, whether it’s their first or their third? What are you working on now?

CS: I hope I speak for most writers when I say it’s one of the highest compliments when a reader tells you that what you worked so hard to do is discernible and, indeed, working! I’m grateful that the texture of them is palpable and functional.

When writing this book, I also read a lot of Carl Phillips. Actually, I’m always reading Carl Phillips. I just read the same poems over and over again and they never tire for me, which is strange since I’ve always thought of myself as someone who thrives best when treading new territory. Sometimes I just sit down are read Silverchest real quick and then I’m like, okay I can move on with my day now. I also keep the voice of Jean Valentine close, and I felt her presence when writing “Little Sparrow, Baby Mole,” especially (and especially when editing it).

To writers who are assembling books of poetry, I’d give a few thoughts. One thing we should always keep in mind is that we are poets, and we mainly write poems. We spend at least 95% of our creative, poet efforts on individual poems. Putting together a book is not an enterprise we are constantly engaged in, and so that muscle might not be developed and/or can naturally atrophy over time. That’s normal, and I hope we all feel a little bit of reassurance knowing this. Ordering a book is not at all similar to writing a poem, and all books require a different kind of order and process. Just as we encounter in our own poems the element of surprise, we should also find that be true when putting a collection together.

Another piece of advice I’d impart is that we should try to allow the poems to dictate the path of the book. It’s important to follow the poems’ lead, always and to try out different structures. I always say there is no one way to order a book of poems, as books of poems carry several throughlines that can be harnessed in terms of trajectory.

TM: What do you think contemporary poetry needs the most right now?

CS: Well, more poets, I suppose. We need more poets who are poets writing their own poetry and what I mean by that is poetry that is singular unto them, that couldn’t have been written unless they had written it. We need unapologetic authenticity and noticeably risk-taking art. You mentioned AI in one of your former questions, and I think what poets need is fellow poets to protect our genre from the superficial, vacuous, and banal. We also need poets who write poetry because they couldn’t otherwise live—poets who are living artists.

Read “Ode to Darnel (Ode to Crocus),” excerpted from The Hungriest Stars