Coercion, Control, and Modern-Day Maternity Homes: An Interview with LIBERTY LOST’s T.J. Raphael

When Abbi Johnson turned thirteen, her father handed her a gift-wrapped box. Inside was a purity ring: a symbolic pledge that Abbi would remain a virgin until she was married.

The gift was embarrassing, but not surprising. Growing up in an evangelical Christian household, Abbi knew that premarital sex was forbidden; this messaging was reinforced at her church and within her homeschool community, where girls were told to dress and behave modestly. So when she became pregnant at sixteen, she expected her parents to be upset. What she didn’t expect was that she’d soon be shipped off to a maternity home two hundred miles away from her family and boyfriend.

To Abbi’s parents, the Liberty Godparent Home – evangelical minister Jerry Falwell’s faith-based residential maternity program for people ages 12-21 – seemed like the best place for their daughter to receive support and guidance throughout her pregnancy. The staff promised that the girls in the home would be well cared for and that in exchange for placing her baby for adoption, Abbi would be rewarded with a full ride scholarship to Liberty University. But once Abbi arrived at the Liberty Godparent Home, she quickly realized that something was off.

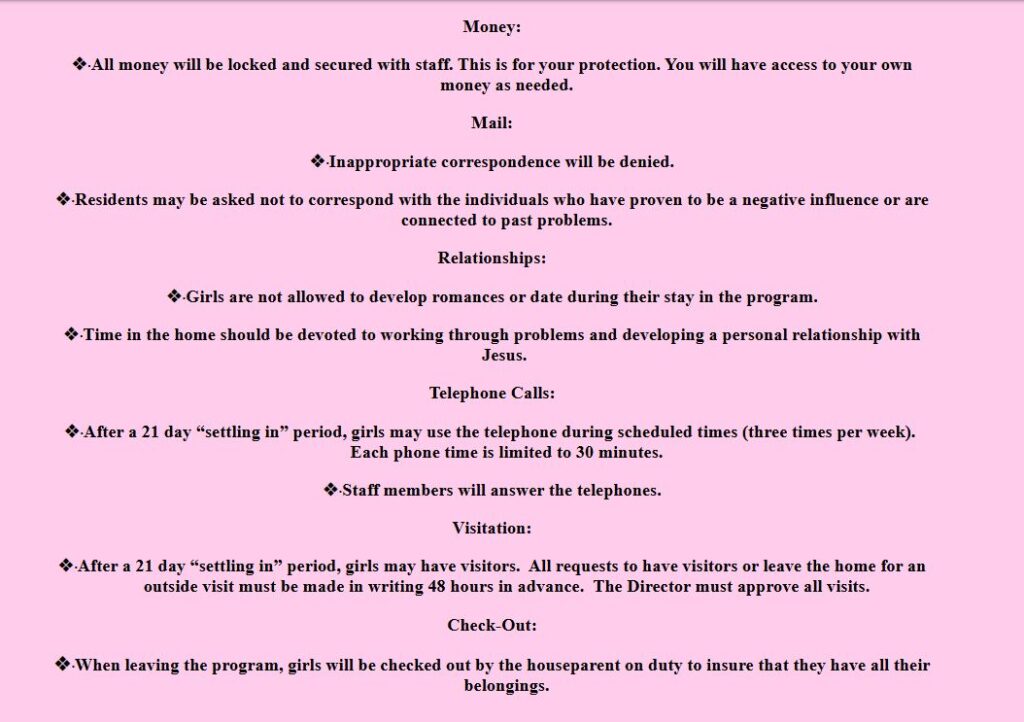

Locked windows and doors. Monitored phone calls. Supervised prenatal appointments. Abbi and the other girls weren’t allowed to discuss their pregnancies with each other, or even to close the doors to their bedrooms. On Sunday mornings, they were trotted out as fundraising props at Falwell’s Thomas Road Baptist Church; the rest of the time, they were sequestered. If a girl broke one of the strict house rules, she was punished with isolation that could last for days. If she tried to leave, the police would be called. With no access to money, no car, and no way of freely communicating with the outside world, Abbi and the other residents were essentially trapped inside the home.

As Abbi’s pregnancy progressed, she began to rethink the adoption. But although the home promised residents a choice between parenting or relinquishing their babies, the pressure to choose adoption was relentless. Despite a growing desire to parent, Abbi was ultimately coerced into signing adoption papers – a traumatic event that she’s still processing today.

This might sound like something from the “Baby Scoop Era,” the pre-Roe time period when maternity homes were commonplace and over 1.5 million babies were taken from young mothers and placed for adoption. But Abbi’s story took place in 2008.

In the Liberty Lost podcast, host, reporter, and series creator T.J. Raphael explores the ethically questionable world of modern-day maternity homes and the complexity of infant adoption in the US through the eyes of former Liberty Godparent Home residents. As I listened to Abbi and others describe their mistreatment at the maternity home that had promised them refuge, a nagging thought persisted: That could have been me.

When I became pregnant during my senior year of high school, I lived just three miles from the Liberty Godparent Home. Like the girls in the podcast who were coerced into relinquishing their babies for adoption, I also received messaging – from authority figures, medical professionals, and society at large – that a teenager like me had no business raising a child. If I wanted to give my baby the best possible chance at life, the reasoning went, then shouldn’t I consider choosing someone else to raise him?

I was lucky. Despite its proximity, I never set foot in the Liberty Godparent Home, and my family respected my decision to parent my child. But if they hadn’t? If my family – like so many others I knew growing up – had attended Thomas Road Baptist Church, where adoption was presented as a redemptive act for the sin of premarital sex and the Liberty Godparent Home was seen as part of “God’s plan” for girls like me? My own teenage pregnancy could have had a very different ending.

Adoption is often framed in terms of individual choice. Yet that framework ignores any number of larger social and political factors that might influence a pregnant person, whether directly or indirectly, to relinquish their baby. After listening to the podcast, it became clear that organizations like the Liberty Godparent Home use their power to their advantage, exploiting pregnant teens at their most vulnerable. And since Roe v. Wade was overturned in 2022, the number of maternity homes across the US has increased by 23%, meaning that more people may soon experience what Abbi went through.

While this series resonated with me on a personal level, it also holds larger relevance amid the current reproductive rights landscape. In order to better understand the significance of modern-day maternity homes in the post-Roe era, I spoke with T.J. Raphael for MUTHA. – Jen Bryant

*

JEN BRYANT: Where did the idea for the Liberty Lost podcast come from, and why was it important to tell this story now?

T.J. RAPHAEL: I was interested in doing something related to reproductive justice following the end of Roe v. Wade, and I started to think about the pre-Roe era when there wasn’t a constitutional right to abortion. When people think about the pre-Roe era, they often think of dangerous back alley abortions. That was definitely a big part of that time period, but it was only one piece of the story. The pre-Roe era was also one of maternity homes, forced birth, and coerced adoption. I thought: In a lot of the country, abortion is going to be banned; are places like maternity homes going to kick into high gear again? And so I decided to veer in that direction.

When I put out a call on social media asking to speak with women who had gone through maternity homes, I expected to hear from older women – Baby Boomers – and I did get lots of emails from them. But I also got an email from Abbi Johnson. When she reached out to me in 2022, she was 31, and she told me that she had gone to this place called the Liberty Godparent Home in 2008. When she told me that it sat on the campus of Liberty University, alarm bells started to go off, because I was familiar with Jerry Falwell’s outsized influence in politics and the controversial history of Liberty University. So it started with Abbi, and then I set out to find other women who had gone through the Godparent Home and began to build out the universe from there.

JB: The Liberty Lost series leads with Abbi’s story; it also features accounts from Toni and Zoe. All three lived at the Liberty Godparent Home during their pregnancies, which occurred between 1991 and 2008. You received a lot of responses when you put out that call for people to share their experiences with maternity homes; what made you choose these stories specifically?

TJR: Abbi’s story was more current – she was there in 2008, and she’s still going through the aftermath of the experience. She’s actually the same age as Toni and Zoe’s daughters. Her son is still a minor today, and as we covered in the podcast, she’s lost contact; she has a closed adoption now. Zoe is now in reunion with her daughter, and Toni never lost her daughter. So from a narrative point of view, following somebody like Abbi on a continuous journey that is still ongoing felt compelling.

Abbi and I are both Millennials. It was shocking to me that something like this could have happened in 2008 and 2009, so that was another reason I focused on Abbi as the lead. I’m really grateful to Abbi for trusting me to tell this story.

JB: While the Liberty Godparent Home claims to “support each individual in making either a parenting or an adoption plan,” the women you spoke with who expressed a desire to parent encountered resistance, coercion, and even expulsion. How many pregnant people who entered the home with a desire to parent actually ended up being allowed to leave with their babies?

TJR: It’s hard to say because the Liberty Godparent Home and the Family Life Services adoption agency, which is connected to the home, refused to do an interview with me. I reached out to them over the course of a year, through every single means of communication – I called, I emailed, I tried to add the director on Facebook and on LinkedIn. I even sent letters via snail mail, and to date, I’ve never received a response. So the stats that I have are very much anecdotal.

Former staffer Brittany Reynolds, who was an intern when Abbi was there and later joined the staff as a house mother, told me that the number was about half and half – that about 50% of residents kept their children and 50% placed. That felt consistent with what Sarah P., who also worked at the home, told me. I think the main difference is whether or not the women who kept their children had support, whether that be parental support or support from friends or other individuals.

But I must note that for the last 30 years, the national rate of pregnant people placing their infants for adoption has hovered around 1%. So if it’s 50% at the Godparent Home, that’s a 5,000% increase over the national average, which is still a huge number considering how unpopular and uncommon adoption is for pretty much everyone who will become pregnant.

JB: How did the Liberty Godparent Home’s silence impact your approach to reporting this story?

TJR: It was incredibly unfortunate. As a journalist, I want to be fair in my reporting. I want to give people the opportunity to respond to things that are being said about them, to defend themselves, to refute those claims.

After reaching out over the course of a year, in the 10 days before we published the podcast, I even wrote and sent – both by email and by snail mail – a list of all the specific claims that were being said: “A former resident told me X, do you have any response?” We went through every single episode of the podcast, compiled every single accusation, and put it there for them in black and white so it wasn’t a question of, “Well, if I knew someone was going to say that, I would have commented…” We wanted to let them feel like they really had the opportunity to do so, and that there would be no surprises when the show published. I also tried to reach out to multiple members of government agencies like Child Protective Services, as well as the Virginia Department of Social Services and the Department of Education, to try to get some clarity on whether these things that happened are legal.

I’m grateful that two Godparent Home staffers did speak to me. But otherwise, in terms of the silence’s impact on my reporting process, I had to very much lean heavily on my sources. For me, it was about trying to suss out consistency. I would interview Abbi, for example, and then I would go to interview Zoe, and I wasn’t telling Zoe, “Oh, here’s what Abbi said to me – is that true for you?” I just let her talk. When these women, decades apart, are reporting the same experience, yet they’d never spoken to each other, it points to a pattern of behavior.

JB: Aside from scholarships to Liberty University, was any support offered to birth parents who went through the home after they placed their babies for adoption?

TJR: Not that I’m aware of. All of the women I spoke to – whether or not they placed – the support ended the day that they gave birth. There didn’t seem to be an ongoing effort to provide support for the feelings of grief or mourning that often happen for birth mothers who place children for adoption. Even if you wind up parenting your child – how are you doing as a teenage mom, or as a young mom in your early 20s? How are you navigating this? Do you need help? Do you need additional resources? That didn’t really seem to be a part of the mission of the Godparent Home at that time. Everyone I spoke to said that when you’re done with the program, they’re done with you, basically.

JB: In episode 6, you spoke with members of Saving Our Sisters, a grassroots organization that provides financial support to pregnant people who are struggling to make ends meet. Listening to those conversations, I was struck by the fact that assistance of just $3,000-$5,000 for these moms can mean the difference between relinquishment and being able to keep their babies. The episode also mentions that 9 in 10 moms who place their babies for adoption do so for financial reasons, with some saying they would have made a different choice if they’d had even an extra $1,000 to $2,000 at the time of their baby’s birth.

Social support systems exist to help low-income parents: WIC, Medicaid, tuition assistance, and so on. But at faith-based maternity homes like the Liberty Godparent Home, teen pregnancy is often framed as a moral issue, and girls aren’t necessarily directed towards the resources that could help them parent if they choose to. Why is that significant?

TJR: In speaking with the past residents of the Liberty Godparent Home, there’s very much a feeling that if you need social services or government assistance, it goes against a lot of cultural and political beliefs that single women who are on social services are bad mothers, that they are doing something wrong. There’s also a cultural belief within religious-based maternity homes that a child can only thrive in the context of a two-parent household – that single motherhood is never a good thing, and that the child would be better off with a two-parent household. And so I think that’s one of the reasons that we don’t see an encouragement of helping a vulnerable single mother stay with her child, because there’s so much stigma around the “welfare mom.” Especially in conservative political circles, there’s a desire to cut these services, and to say as a society we do not owe parents any kind of help.

One of the reasons that Saving Our Sisters provides direct financial assistance is because even for the programs that exist, especially housing programs, the wait list can be up to a year long. If you’re delivering in a month, you might be at the bottom of that list.

In the United States, we demonize poor people whether or not they’re pregnant. The Trump administration just made huge budget cuts to social service programs. There doesn’t really seem to be an interest or an appetite for supporting poor families and especially poor women, and oftentimes the households that are most dependent on government services are led by single mothers. When we think about why places do not support low-income pregnant women, I think it unfortunately comes back to cultural attitudes and beliefs.

JB: The anti-choice movement often talks about the negative impact that getting an abortion might have on a person’s mental and emotional health, despite evidence to the contrary. However, they’re largely silent about the full spectrum of emotions that women who have placed children for adoption might experience. Why do you think that there’s still such a taboo around this subject?

TJR: In religious context, adoption is seen as godly, because it’s helping to spread the gospel and recruit new followers to the religion. From a cultural standpoint, there is an inherent idea that you’re saving this baby. You’re saving their soul, you’re helping them go to that idealistic nuclear family with two parents who are often heterosexual, who are often white, and so I don’t think that there is a big appetite to draw attention to the very real lifelong grief and feelings of mourning that birth mothers experience.

Whether they’re faith-based or not, adoption agencies also sell birth mothers on the idea that “You can have this open adoption, you’ll be part of your child’s life, and you’ll be like one gigantic family.” For a lot of adoptive parents, even if they want to have some contact, they don’t necessarily want a co-parenting relationship. The adoption industry thrives by selling a fairytale narrative: Your child can have everything that you can’t provide, you can continue to live your life, and everything will be great. Introducing the very real, complicated, messy, and painful feelings surrounding adoption for birth parents – and for adopted people, who report higher rates of suicide and mental health issues – complicates that. I don’t think as many people might be interested if they understood all of the nuances that come with adoption.

JB: What were your thoughts on maternity homes when you began working on this project, and did they change at all by the time you finished?

TJR: I thought of maternity homes as a thing of the past. I didn’t realize that they actually never went away in certain communities. And beyond maternity homes, working on this project has radically changed my views about infant adoption. We didn’t touch on adoption through the foster care system or adoption of older kids, and there are definitely children out there that need help, support, and safe, stable homes. But I didn’t think critically about infant adoption – what drives a woman to gestate a full pregnancy to term and then permanently separate from that child. And I think once we start examining why infant adoption happens, the myths we tell ourselves about adoption begin to unravel very quickly.

Like a lot of other people, I really only interacted with the idea of adoption through media that portrays it as this beautiful thing. As I said in the show, we often see birth mothers very briefly, and then they’re just guided offscreen, never to be heard from again. That was my idea of adoption – it was through the lens of adoptive parents, not birth mothers. And I’m very grateful to have worked on this, because it’s radically changed my perspective in a lot of ways.

JB: Since Roe v. Wade was overturned in 2022, the number of maternity homes operating in the US has risen by nearly a quarter. With abortion access banned or severely restricted in many states across the country, it seems likely that their numbers will continue to rise. Given what you’ve learned during the course of your investigation and reporting, do you think it’s ever possible for maternity homes to operate ethically? Or will there always be a power imbalance that’s inherently part of that model?

TJR: I think that it is possible for maternity homes to operate ethically. Where things get dicey is the power structures behind them.

In theory, maternity homes are wonderful – they serve a vital need, because who goes to a maternity home? It’s a pregnant woman or person who does not have a safe or stable place to live. Maybe that’s because of a domestic violence situation, or their partner is out of the picture; maybe it’s because their family isn’t supportive; maybe they’re working a low-income job that doesn’t give them maternity leave; maybe they have a health complication. But they need shelter, they’re pregnant, and they’re literally at the most vulnerable period of their lives.

So I do think we need more places for pregnant people to go for safe harbor, food, medical services, community, and support. Where that gets ethically murky is if they are run by conservative religious institutions with worldviews that single motherhood is bad, that sex outside of marriage is a sin, and that people need to be redeemed for that sin.

There are nearly 500 maternity homes in the US. More than a third are affiliated with Heartbeat International, which is one of the world’s largest anti-abortion organizations. We play a tape in the series of one of their vice presidents saying adoption is a redemptive choice. And I don’t think we need to be redeeming women for having sex outside of marriage; we don’t need to think of adoption as a redemption plan. So yeah, I guess my feelings are very complicated.

In the United States, Planned Parenthood is a household name – for abortion, for contraceptives, for STD testing. We have no household name in progressive spaces for women in crisis who want to keep and parent their children. And so as I’ve worked on this series, I’ve also come to view this as a failing on the left, for progressives, because maternity homes have largely been co-opted. It’s become a vacuum of conservative religious institutions running these places, and we need more neutral secular places to help support vulnerable pregnant women.

Cover photo courtesy of Wondery.