Woman Interrupted: The Hidden History of a Doctor Silenced by Stigma and Sexism

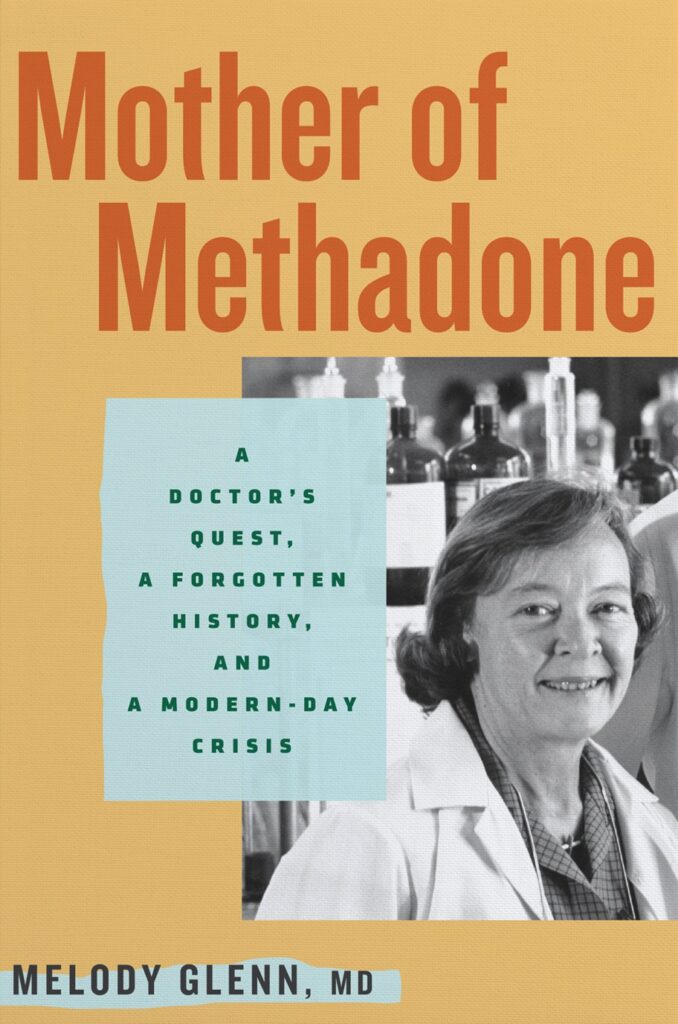

Mother of Methadone: A Doctor’s Quest, a Forgotten History, and a Modern-Day Crisis (Beacon Press, 2025) is the story of two women doctors, living decades apart, with a shared mission to treat those struggling with heroin addiction. Finding herself drawn to addiction recovery, Dr. Melody Glenn, an associate professor of addiction and emergency medicine at the University of Arizona, realized not only were her patients stigmatized for their drug use but so were the doctors who treated them.

Mystified why the most effective harm reduction medications, methadone and buprenorphine, were being treated as the problem and not the solution, Dr. Glenn’s research led her to Dr. Marie Nyswander, who defied the DEA and the medical community in the 1960s as she codeveloped methadone maintenance for heroin addiction. Hailed by addiction specialists as a “discovery as monumental as the discovery of penicillin,” Dr. Nyswander risked her medical license, career, and jail as she continued her work—only to have her groundbreaking research credited to the men around her.

Dr. Melody Glenn weaves together the story of two doctors on a mission to help, heal, and reduce the harm that often accompanies addiction recovery. She gives a voice to Marie, the revolutionary researcher who didn’t recognize she was being silenced because the work of women during her time was only seen if a man showed it to the world and only heard if his voice shared it.

Although I’m an English teacher by trade and not connected to the field of medicine, I found myself so engaged in the story of these women that my red pen annotated page after page, asking questions, looking for answers, and underlining passages that felt both hopeful and hopeless because—even after all these decades—women must still push to be included in the spaces and places where we know our voices are valuable.

Both a bold biography and a moving memoir, Mother of Methadone moves the reader from Marie to Melody, two women called to medicine who risk reputation and career as they break down the barriers built around addiction treatment and recovery by the medical community and the government. – Bridey Thelen-Heidel

*

BRIDEY THELEN-HEIDEL: “What haunts us? What hunts us? What are we hunting?” Your poetry professor, Truong Tran, at Mills College, asked you this when you decided to go back to school after becoming a doctor. He then said, “The answer to that is our life’s work.”

What was it about Dr. Marie Nyswander’s story that haunted you enough that you felt you needed to write it?

DR. MELODY GLENN: Tran’s quote really captured the hidden forces that propelled me to write this book. When I first started writing, I didn’t yet know what the finished product would look like, I just knew I was writing in response to the questions that haunted me: Why was there so much stigma against methadone, one of the most effective treatments we have for a chronic disease? Has it always been that way? Despite the media outcry around the opioid epidemic, why aren’t we increasing access to the medications that halve the mortality rate? Overdose is not inevitable and opioid use disorder is not a helpless cause. We have proven, evidence-based solutions, yet there is not enough political will to enact them – why? And, on a personal note, what does it mean to be a woman in medicine? To be a doctor who wants to make the world better, but doesn’t want to fall into the “savior trope” so readily ascribed to physicians? To be a physician fighting the double stigma of being a woman and advocating for a group of people who the world would rather just forget? It seemed like discovering Marie’s story might somehow unlock the answers to all those questions, so I began to dig.

BTH: You hunted down Marie’s story for years, writing, “I owed at least that much to Marie, as well as to the women who are still to come. Until flawed histories are corrected to award credit where it is due, we cannot truly move forward.” Marie, herself, said she never dealt with sexism during her career, but your subtitle, “A Forgotten History,” acknowledges that her life’s work was essentially credited to the men around her. Two recent films, Hidden Figures and The Six Triple Eight also told forgotten histories.

Why do you think we’re so invested in giving women their “flowers” after all these years? Why is it important that we hunt down these stories?

MG: Yes! Despite the fact that Dr Marie Nyswander was a leading addiction expert and one of the few physicians who had ever worked with methadone, many of her peers believed that methadone maintenance was developed by her husband, a researcher who focused on metabolic diseases like obesity and diabetes, and that Marie was just along for the ride. Could they not imagine a world in which women scientists made such significant discoveries?

And thank you for linking Marie’s example to other forgotten women scientists – ascribing women’s innovation to the men around them was not an isolated incident, yet it is very easy to frame it as such. In fact, framing a systemic issue as a personal failing is core part of the sexism playbook, a key way to let misogyny off the hook. To highlight these women’s stories is a way to shine a light in the ways in which sexism operates, both then and now. If we can’t even see it, how can we move beyond it?

BTH: Do you feel like the area of addiction recovery treatment hunted you? Do you think it found you because it needed you to do the important—and brave—work of discovery and advocacy as it did Marie?

MG: It certainly felt like addiction medicine chose me, and I’m glad it did. After I finished a decade of medical training (2 years of premed, 4 years of medical school, 3 years of residency, 1 year of fellowship), I was knee-deep in burnout. But once I discovered that we had very effective treatments for opioid addiction—buprenorphine and methadone—I found the purpose that my professional life had been lacking. In a sense, addiction medicine saved me, just like it saved Marie, just like it has the potential to save others.

BTH: Marie’s story, including her life’s work in the field of addiction treatment for “PWUD”—your acronym for people who use drugs—felt both aspirational and inspirational as you told your story of being a young woman in medicine. What part of Marie’s work and research felt aspirational in terms of your career and the life-changing work you felt called to do around addiction treatment?

MG: So often, I feel like I am the crazy one. Although we are more apt to call addiction a disease these days, by and large, the medical establishment doesn’t really treat it like one. Although fatal overdose is a leading cause of death in this country, healthcare doesn’t pull out all the stops for addiction like it does for trauma, cardiac arrests, strokes, etcetera. Instead, many hospitals don’t even have an addiction specialist on staff, much less social workers or peer recovery specialists available to assist patients with chaotic drug use. And so our patients fall through the cracks, and most overdose survivors are never offered the treatments that could halve their risk of death. But when I speak out against these issues, I am often made to feel like I am causing trouble or being ridiculous (a ridiculous woman?). It was so reaffirming for me to see that Marie had experienced the same kind of treatment. The problem wasn’t really me – the problem was a stigmatizing system unwilling to change, the same system that was around in Marie’s day. And yet, she managed to make a huge difference despite all the barriers.

BTH: You mention that not only were patients stigmatized for their addiction, but the doctors who treated them were as well. How did Marie’s work inspire you to continue in the field of addiction treatment when you could have gone a different—and likely more acceptable and understood—field of medicine?

MG: It was helpful to find a name for what was happening to me at work: Every time my research was deemed impractical, every time my emails to supervisors went unanswered, every time my “non-academic” writing was labeled as silly, it was largely because stigma against people who use drugs was spilling over into how addiction medicine itself was perceived. Because people who use drugs were not seen as important or profitable, neither was my work (at least to those in powerful positions). Before I realized that connection, I often blamed myself – I just wasn’t a good enough academic or physician. But seeing how this happened to Marie gave me the perspective I needed to keep going.

BTH: Although Marie claims she did not deal with sexism, you have dealt with it in your career—as a young mom who was still breastfeeding and as a woman in medicine whose work was questioned and somewhat disregarded. Marie seemed to be a lighthouse for you when your work felt difficult and isolating, and I wondered how you show up for young women in medicine?

MG: Part of the reason I wanted to share the intimate details of my own life was so that women in the early stages of their medical career wouldn’t feel so alone. When hospitals and medical residencies were created, they weren’t designed with us in mind. So is it any surprise that they fail to support us, especially if we are breastfeeding or have young children? But because so many of us feel like our struggles are related to our own inadequacies, we don’t tell anybody about them. If we do, they might see what an imposter we really are! But there is a power in breaking that silence. Although I was initially very hesitant to reveal some of my vulnerabilities in such a public way, I thought it was an important step towards creating a healthier culture in healthcare.

And as I have stepped into more of a leadership position myself, I try to encourage the passion of trainees and be available as a mentor that supports their goals. Although I write a lot about the experience of being a woman in medicine, a lot of men have also resonated with my work. Being kind, making healthcare more family-friendly, and striving for a better future is good for everyone, regardless of your gender.

BTH: When given the opportunity, what advice do you give them when they are facing obstacles you might have overcome earlier in your career?

MG: If you keep your head down and stay focused on your own work/truth, you can make a lot of progress. Pleasant persistence has gotten me pretty far.

BTH: You write about the stigma around addiction—not only for the PWUD but also the doctors who treat them. You write, “Instead of facing the possibility that we didn’t know everything, we blamed the patients.”

As a kid who grew up in the house everyone was afraid of in our neighborhood, I understand the dangers and isolation of that stigmatization of those we don’t understand or maybe are afraid of. Do you think we stigmatize things and people we don’t understand—or don’t want to understand—because it somehow lets us off the hook from feeling that we need to help them?

MG: Yes, 100%. Stigmatizing, scapegoating, and dehumanizing others are all related. At their core, they are psychological coping mechanisms that have real costs.

Healthcare workers face a lot of moral distress and injury in their job. For example, I care for a patient whose main trigger to drink is her hip pain, but her orthopedic surgeon won’t operate until an anesthesiologist clears her for surgery, but the anesthesiologist won’t clear her for surgery until she has a cardiac catheter, but the insurance company has decided they won’t cover the cost of the cath, so she continues to drink. Over time, these moral distresses add up, potentially turning into moral injury. For healthcare workers, focusing on what we can change and ignoring the systemic problems that we cannot is a method of self-preservation. But in terms of opioid addiction, we don’t need to ignore it – we have real solutions! And once I realized that, my professional relationship with people who use drugs completely shifted. Instead of feeling distressed by my inability to do anything, now I feel fulfilled. In a very selfish sense, practitioners should embrace addiction medicine as a way to prevent their own burnout.

BTH: Does the stigma protect us from the compassion or the empathy that might compel us to want to help, knowing that help may be expensive financially or even emotionally?

MG: Maybe for some, but I think this is a false choice. There are very real ways to help that don’t cost a thing, and make us feel better in the process. Yet, I do think that denying and ignoring the problem protects us, at least superficially, from lifting up the metaphorical rug. If you write off PWUD as irresponsible addicts, then you can ignore all the systemic issues that contribute to addiction: poverty, racism, inequality, sexism, child abuse, intergenerational trauma, etc – issues that perhaps some of us benefit from.

BTH: What is the danger for us as a society if we continue to stigmatize “the other” who we don’t want to deal with?

MG: Most obviously, we will continue to lose lives and the overdose epidemic will only worsen. On a more global scale, this tendency to dehumanize others is what ultimately leads to wars. Do I think that ignoring the overdose epidemic will lead to war? No, of course not, but they share the same psychological processes, the same refusal to face the dark underbellies we preferred didn’t exist. But if we just faced the problem, we would all be better off. In the words of the KPop Demon Hunters, “I’m done hidin’, now I’m shinin’ like I’m born to be.” If the healthcare system decided to do something about opioid use disorder, if practitioners were willing to start buprenorphine and methadone on eligible patients, there would be less overdoses and less healthcare burnout. Everybody would win.

BTH: What impact do you hope your memoir will have on those working in or funding the field of addiction treatment?

MG: I hope this book reaches some of the skeptics, some of the healthcare providers and policy makers who are in a similar place to where I was a few years ago, and that the intimacy of memoir allows empathy to find a way into their hearts in a way that the facts and data could not. If reading a book over a few hours could help them bypass the years it took me to go through this journey, wouldn’t that be great? Ultimately, I hope that my book leads to policy change that increases access to buprenorphine/methadone and harm reduction and prioritizes treatment over incarceration.

Dr. Melody Glenn is the author of Mother of Methadone, a hybrid memoir/biography published by Beacon Press in July of 2025 that weaves her story of becoming an addiction physician with that of Dr. Marie Nyswander, the radical physician who developed methadone maintenance in the 1960’s. An MFA alum from Mills College, her writing has appeared or is forthcoming in Mutha, River Teeth, Salon, Time, Literary Hub, and the Believer Magazine. She is also an emergency, addiction, and EMS physician at the University of Arizona College of Medicine in Tucson, Arizona, and the mother of two young girls.