Eulogy for a Life That Wasn’t

I couldn’t really get excited until the morning they were going to put you inside me. I had tried not to imagine what your smile might look like, how it might feel to hold you, how relieved I would be when you finally arrived. It was too painful to hope, to dream.

But that morning, I did imagine those things. I paced the sunny Airbnb and let myself feel it all. I felt a new lightness and a small, tentative hope that maybe this whole big gamble would work. I felt connected to my dead father and the legacy of his love I wanted to pass on to you. I felt brave for doing this on my own, for figuring out how to manage my fear of needles enough to give myself 28 injections.

I had done all the hard parts — the finding of sperm, the six failed intrauterine inseminations, the wrangling of insurance, the many early-morning, two-hour drives to the IVF clinic. If you are queer and single and 37, you have to really want it. And I really, really wanted it. Wanted you.

Now this, the embryo transfer, was the easy part! All the strangers on the internet said so. I didn’t even need a friend to come with me because it was so simple and quick, I wouldn’t need any sedation. A 70% chance of a live birth, the doctor said. Those are pretty good odds, and for a brief window that morning they barreled right through the calcified refusal to let myself hope.

Before I tell you about the day they were going to put you inside me, I want to tell you that I loved another baby, once. Though the honest truth is that when they were an embryo and then a fetus, I didn’t feel love or hope. I felt fear and resentment and envy. When I was informed of their nascent existence, I cried — and not in the happy-tears kind of way. I felt ashamed of that. I was supposed to be happy about that pregnancy and I never was.

I had fallen unexpectedly and overwhelmingly in love with someone who was ten years into a committed partnership that included iron-clad baby-making plans. We had, with much negotiation and heartache, found a way for my new love to be with us both — me, the new girlfriend, and her, the wife who was now newly pregnant.

I watched that baby grow in the wife’s belly and ached for the experience, longing for my own potential child. I watched as she stroked the spot where her baby was growing, cradling them fiercely and gently. Watched our shared partner gravitate toward that growing stomach like a magnet. Watched the ultrasound images accumulate on the fridge. When her new breast pump arrived, and she talked about how she would nourish this baby even while apart, I cried. I wish I could tell you I cried in the next room, but I cried right there next to the breast pump. Everyone gets excited and hopeful about babies — they are celebratory and cheerful and uncomplicated about it. Most of the time I wanted to scream.

*

The IVF clinic’s ultrasound tech had warned me how enormous the NICU-like incubator was, but when they rolled you into the small exam room, I still said “whoa.”

“I told you,” the ultrasound tech said. “Nobody ever believes me about how big it is.”

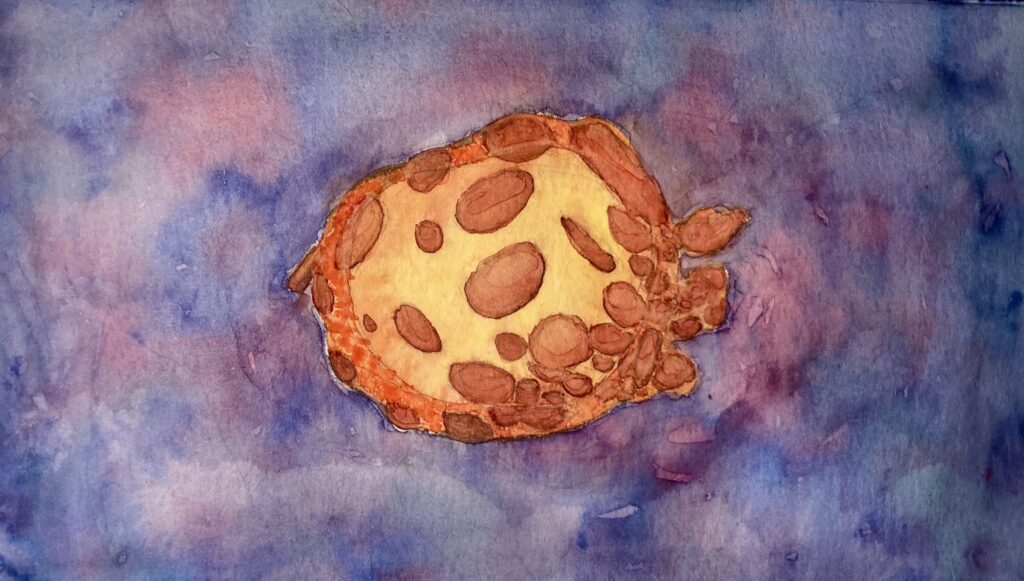

They put an image of you up on a screen, and that is how we met. The embryologist said you were perfect and beautiful and asked if I wanted a photo. I did.

“I don’t know what an embryo is supposed to look like,” I said.

“It’s supposed to look like that,” the embryologist said, pointing at the screen with calm satisfaction and maybe pride. I suppose she made you as much as I did.

I was lying on the exam table in a fancier-than-usual medical gown, a speculum inside me. You weren’t visible to the naked eye. You were a small bunch of cells, really not very many at all, and had grown for five days in this world. You weren’t a life or a person or a human, and it’s hard to know how to write about you without sounding like I oppose abortion, like I agree with the terrifyingly theocratic judges in Alabama who erroneously ruled that you are the equivalent of a minor child. No. I would defend anyone’s right to destroy their embryo as ferociously as I pursued your creation. I hope you understand.

You were determined and resilient, had already made it through a daunting gauntlet. A sperm and an egg had to combine in the right way, and then you had to keep dividing your cells in the right way at the right speed, and a lot of times that doesn’t work. There’s so much attrition at every stage — egg maturation, fertilization, day 3, day 5 — that people on the internet call it the Hunger Games, which I find hilarious and aptly harrowing.

But you made it to day 5 — you were a blastocyst! — and I was already proud. I called you The Little Embryo That Could because you were the only one that made it. And you got your first two As, which is apparently how they grade embryo quality, one letter grade for the would-be fetus and one for the part that would become the placenta. You aced both! I promised myself I wouldn’t care about letter grades once you were born, just whether you felt safe enough to be your wholest, truest self. But for now, I let myself be proud. You were a possibility, a potential, a potent receptacle for projection and dreams, and I was already in love with everything you might be.

*

I wasn’t in love with the possibility and potential of the other baby. I saw them as a threat to my growing relationship with their abba — the Hebrew word for father — with whom I was wildly, want-to-be-next-to-you-at-the-end-of-the-world in love. I saw that baby as a threat to my own desire to be a parent, which had been temporarily dormant but thoroughly reawakened by falling in love and watching my partner’s wife get pregnant.

That baby was born right before a global pandemic that changed most everything about life as we knew it. When their parents’ original childcare plan fell apart, I stepped in to do more infant care than I’d planned and then I slowly, almost reluctantly, fell in love with that little baby. I became a diaper-changing pro and woke easily when the baby stirred at night. I endlessly paced the kitchen while their bottle warmed and sang them songs my mom had sung to me, mostly old show tunes and “The Friendly Beasts,” a Christmas favorite about all the animals present at Jesus’ birth. I fed them their mom’s breast milk from a bottle and they would fall asleep on me while I looked at their perfect, miraculous beauty and marveled at their existence.

I did fall in love. And then I left, to try to make you.

*

I don’t remember the first sign of trouble. Maybe the doctor couldn’t thread the catheter as planned. Perhaps she had to reposition the speculum. It felt like she was driving stick shift in my cervix. Widen the speculum, reinsert the catheter, take it out, give you back to the embryologist, try again with a different catheter. Repeat and repeat.

I started to breathe deeply to avoid panicking. Breathe into my belly, where the doctor was trying to put you. I know that’s not anatomically precise, but it feels like the same place: hands on the abdomen to indicate stomach pain but also to announce a pregnancy.

I asked what the backup plan was because it helps me to have backup plans, and I had started to suspect things were going awry. The doctor said they might need to refreeze you and try again later, and that this reduced the chances of a live birth by about 15%. She said they refreeze embryos not infrequently and it would be okay.

This is what was happening: she kept getting stuck on a mysterious obstruction in my uterus, which had not shown up on the extensive imaging she’d done of every inch of my insides. She said, “I’ve never gotten stuck here before” which is not what you want your highly acclaimed IVF doctor to say when she is trying to deposit your only embryo into your 37-year-old uterus, after you have shot yourself up with the maximum possible dosage of fertility drugs.

By the time she emerged to talk to me again, I was crying and too warm and my whole body was vibrating. I didn’t want to refreeze you. I had done so much to get to this tenuous, miraculous juncture and I couldn’t believe this was happening. This was supposed to be the easy part! And yet, I also could believe it, because I usually assume bad things will happen. It’s not how I want to parent you. I don’t want to teach you to assume the worst. I’m working on it.

The doctor took the catheter out of me — the catheter with you inside it — so the embryologist could put you back in the big incubator and you could pretend you were in my fallopian tube. Then she started to explain what would happen next.

*

When the other baby was learning to walk, I was the exact right height to endlessly toddle around with them holding my hands as we did loop after loop of a small apartment in the cold northern winter. I loved how they imperiously grabbed onto my fingers and dragged me after them, never imagining I wouldn’t follow.

I would pick them up and we would walk around the kitchen together while they asked me to name every kitchen gadget over and over again, insatiably curious and wanting to soak it all in. “That’s a measuring spoon. That’s a spatula. That’s the coffee maker that makes the loud noise.”

Once they could walk on their own, I learned to listen for when their “yes, please chase me” giggles turned to “I’m overstimulated, please stop” screeches. I have never felt a sweetness like I did when they presumptuously patted the back of my thighs in the particular way that meant “pick me up!” Or when they got scared by a knock on the door and ran behind me and grabbed my legs for protection. They called me “Na” and then “Nya Nya.” Sometimes they asked for me in the morning when their abba got them from their crib, even before they asked for their mom. I felt secretly, smugly satisfied about this.

I marveled at their curiosity, their gentleness, their first steps, their brave toddling, their hunger to communicate, how they learned to play “catch” by shuttling a ball over and over again between me and their abba.

But here’s the truth: I never loved them like their parents did. They would sit in my lap while I read them Love Makes a Family and they learned about how beautifully expansive family can be, how love and support and consistency matter more than genetics and biology and blood. All the while, my traitorous heart clanged with the ceaseless tolling: I want MY baby, my baby, my baby.

*

The doctor took the speculum out of my body. I sat up and took more deep breaths while the ultrasound tech put a cold pack on my neck so I didn’t pass out.

I tried to listen to the doctor explain about refreezing you. She wasn’t able to place you in the optimal location in my uterus. She wanted to give you the best chance she could, given there was only one of you, and she had done a lot of “manipulating” and this didn’t make for an ideal implantation environment for you.

I was starting to ask a question when the embryologist, standing at that big incubator, said: “Dr. Winston, I’m not seeing the embryo.”

*

The last time I saw the other baby, they were toddling away from me with their mom, waving and cheerfully saying “byeeeee,” which they took every opportunity to say because it was one of their newest words. They were too young to understand that this was GOODBYE. After they left, I knelt in the foyer and said “I’m sorry” again and again to the empty space.

I could only drive away because the alternative was worse. I had waited — sometimes patiently, sometimes fitfully — and hoped that someday it would be my turn, that this unconventional and expansive dream of family could make room for my baby, too. But it had become wrenchingly clear that was not to be. A little after Christmas, my partner had finally spit it out: “No, I’m not going to change my mind about wanting to have a kid with you.” So as my partner and their wife planned a second pregnancy, I’d had a choice to make: stay in this family as it was and forego my own baby-making dreams, or leave.

I was something between a nanny and a step-parent and an aunt, and none of it was enough. But the baby didn’t know that — they just knew I would patiently name the kitchen gadgets, and always remembered their favorite page in Quick as a Cricket. They didn’t understand they weren’t “mine,” which is an odd word we use about other humans, but which I wanted anyway. They didn’t care about the fraught state of my relationship with their abba, or my soul-shriveling envy towards their mom. They just knew I was a safe human who lived with them and loved them. Not that alongside the sweetness and tenderness of loving them, I felt a monstrous haunting echo of the baby who wasn’t real yet but whom I wanted more than them.

*

At the IVF clinic, the doctor calmly told me that it seemed, given that you were not in the catheter as expected, you were in my uterus after all. It was like when my mom said my dad was going to die: I had to check to make sure I was hearing it right. The mind can’t process overwhelmingly bad news all in one go. “I think what you’re telling me is that the embryo is in my uterus even though you didn’t want it to be there,” I said.

The doctor said yes, it seemed that with all of the manipulating she’d had to do, you had gotten sucked into my uterus. She said there was mucus on the tip of the catheter and maybe that was how, maybe the mucus had created suction. Impossible to know for sure.

I asked her how she knew you weren’t, say, on the floor of the exam room, hadn’t just dropped out of the catheter during all of the to-and-froing from the incubator. “Embryos are sticky and they don’t just drop out of catheters, they need to be pushed out or sucked out,” she said.

You (probably) weren’t on the floor of that exam room, but you weren’t in the right spot in my uterus, either. And in 10 days a nurse will call me and confirm what I already know to be true, that the cells of you have composted inside me and that is the end of you.

I want you to know that it is not your fault. It was not to be, and I wish you well on your journey back to the stardust. I thank you for teaching me new lessons about the power of longing and of hope, and how to bear the unbearable. I loved what you might have been. Maybe there will be another of you, another constellation of cells that makes it through the gauntlet and grows into an actual human child and not just the enormous dream of my heart. And maybe not.

2 Responses to Eulogy for a Life That Wasn’t