That Is Who You Are

“Who knows what’s good or bad?”

—-Taoist Parable

On any given day, I vacillate between wanting to be a tenure track faculty member in a nationally renowned MFA program or a part-time employee for the grounds crew in the village where I live, watering petunias in the downtown square. Other times I just want to be home, relaxing on the floor in a cardboard fort, watching Pixar films with both of my children nestled around me. But I don’t have to make a choice anymore.

Did I perform poorly? I wrote with tears in my eyes in an email to a person I had never met. I had been an online adjunct for two and a half years for a university that awarded Associate’s degrees to students who were incarcerated. Prior to that, I paced around classrooms teaching writing in West Virginia, Missouri, South Korea, and finally Oklahoma. I loved teaching, and I worked hard at it, because I believe in the power of language to help us understand ourselves better and feel less alone.

When I started teaching online, I stayed up grading far later than I should have, providing extensive feedback to each student essay because that was all I could do. We couldn’t meet; we couldn’t see each other. Restrictions for the program were tight, and students had little access to resources. I threw myself into their essays, providing far more critique than I had when I taught in a physical classroom and my students had access to office hours, an enormous university library, the Internet, and the freedom that comes with an everyday life outside of a prison cell. My students often told me how much I helped them and thanked me for treating them like a person.

In the months leading up to my abrupt dismissal, everything went as it normally did. I was asked what I wanted to teach, but then noticed I wasn’t receiving weekly updates in my inbox anymore. I was never warned that I might not get a section for the summer — what adjunct is? — so when I didn’t, I questioned everything I did over the course of the past two and a half years.

Did I not grade quickly enough?

Was it because of that grade appeal? The first one in my 12 years of teaching?

Is it because my name is at the end of the alphabet?

Did applying for a full time position teaching creative writing in the

department that I didn’t end up getting anyway lead them to—- rightfully so—-

question my allegiance to a job that pays $800 a month?

Did I complain too loudly about Sherman Alexie being on the syllabus?

I know how to live on a budget. It’s like dieting, except with money, and you have to do it or else you go to jail. I grew up on a farm with four siblings and a mother who watered down the ketchup. Later on I was a Graduate Teaching Assistant in West Virginia, washing dishes at Panera at night. When I was in my thirties and my husband and I bought a house, we sought out a mortgage that we could pay with one income. You buy the cheap coffee, the cheap bread, the cheap tuna. Cut the memberships. Don’t buy any apps. Everyone grows their hair long. Stay inside your cardboard fort and lean on that rich, internal life of yours that led you to be an English major in the first place.

I don’t fault my university. They are just doing what every other school does:

building programs on the backs of adjuncts that they hire in bulk when they

need them and quietly remove from the email list when they don’t. I signed up

for it with glee, well aware of the risks involved, of the strain it would put

on my mental health, of the nights and weekends I would have to sacrifice, but

grateful that I would be able to pay my bills with ease, that I could sign Mae

up for dance class, that I could buy the good shoes for Wilder to learn to walk

in, that I wouldn’t have to scour garage sales and clearance racks. And for two

and a half years, I had that. I was able to be home with my kids and keep the

loosest of footholds in my professional field so that I might have a chance at

real employment when they were in school. I knew my university could decide at

any time that they didn’t need me, and I held my breath at the end of every

term, like every adjunct does.

*

In the memories I have of my childhood, my mother is rarely at rest. I

remember her hurrying: Leaning forward as she pushed the wheelbarrow down the

driveway to finish her chores, hustling up the stairs to take a shower, running

out the door to drive to the pizza shop where she worked nights. In first

grade, I drew a picture of her sleeping in her bed. The assignment was to

depict our parents doing something that they loved.

Our mother never spoke about craving sleep. Rather, it was something we all

felt and saw. I vividly recall how she and my dad would stay seated at the

table after dinner, push their plates away, then fall asleep with their

foreheads resting atop their folded arms. My siblings and I would gaze at them

from the living room, astonished.

Once

we took a picture, and it’s like that photograph was at the end of a branding

iron, burned into memory, smoke hissing up at the edges. No one had cleared the

table yet, and they slept there, slumped among the cups on their side and

dishes drying with gravy.

*

I had never been to the campus, so one rainy morning with nothing to do I

drove the thirty minutes down the road and pointed it out to my kids in the

backseat.

“Look,” I said, pride at the edge of my voice. “That’s where mommy works. Kind of.”

I had avoided looking for full time jobs. I didn’t want the temptation, didn’t want another decision to think about. I wanted to be home with Wilder the way I had with Mae, but I missed teaching face-to-face, the energy of a college campus, and I tricked myself into thinking that with a professor’s schedule I wouldn’t be gone that much. I also felt guilty that I wasn’t contributing enough to our financial future and reasoned that if I got a jumpstart on working, by the time my kids were older, I would be making substantial money.

That’s how I found myself clicking through job ads, and when I saw that the

university where I currently worked was looking for a tenure track creative

writing professor with experience teaching composition, I felt that tug.

“Do I do it?” I asked my mother.

“Yes,” she said. “We’ll figure it out.”

Almost everyone told me the same thing. “It’s too good of an opportunity,” my

husband said.

The only person that thought I would be crazy to apply for a full time

teaching job was one of my sisters.

“Do you really want to do that?” she asked over the phone.

“No,” I said. “Probably not.”

I wouldn’t call my life relaxed, but I do love the pace of our days, that, if

we want to, we can just go to the aquarium. Did I want to trade that in? In my

heart, I knew the answer was no, but I applied anyway. If I am being completely

honest, I know the reason why: I wanted something bigger, and my children

weren’t enough.

*

On my last day of teaching in a physical room, I sat at a desk and wept with

one of my students after class had been dismissed, the Oklahoma sun beating

through the windows. She was a good student with a slight build that belied

her, and I often used her essays as an example. Her writing was like her:

straightforward, precise, detailed when it needed to be. She had just found out

her husband was having an affair. When she mentioned how worried she was about

her kids, I started to cry.

“I’m so sorry,” I whispered.

In my years of teaching, I had heard innumerable stories that shredded my heart,

but I never broke down. I taught at regional universities in rural areas of the

country, my students often first-generation college students, working multiple

jobs, raising their own kids. They brought their books to class in plastic

bags. I held their babies for them on the days when they gave their

presentations and couldn’t find a sitter. I read their essays alone in my

office, my hand over my mouth. I bolted down the hall to my department chair

after one email from a student saying she felt like she was trudging through

sludge and I didn’t think she could do it anymore. I listened to their stories

about testicular cancer, relationships gone to hell, rape. I attended sessions

on how to make my office a safe place, and put a sticker on my door saying that

it was. I got wrapped up in their lives because I saw no way around it.

Universities obsess over retention rates, so it was our duty to make sure

students came to class. I knew them, and I loved them. And I was able to hold

it all together until that day in the nearly empty building, 2:30 in the

afternoon on the last day of class before summer, when I couldn’t anymore.

In

August my husband got an unexpected job offer, so we packed up our 8 month old

daughter for Cleveland and I never saw those students again.

*

My mother has converted her massive farmhouse into a grandchild’s dreamworld.

My old bedroom brims with toys from our youth and others she picks up from her

carefully curated list of garage sales.

“I haven’t had a chance to clean up,” she says, leaning in the doorway to the

kitchen with her overalls on. “I had a sheep jump the fence.”

I read an article once that said parents, when asked what they thought their

kids wanted more of from them, mostly replied “more time.” When they asked the

kids what they wanted, they mostly said they wanted their parents to be “less

tired and stressed.” I used to try to remember this, just sitting with my kids

while they played, made messes, bickered, sobbed. Now, though, I can’t help but

think: did anyone ask the parents what they want?

“Did you eat?” my mother asks. “I can make burgers.”

*

Without knowing it, I started to think of myself in mechanical terms, a human

Roomba, picking up after everyone around me, taking in every mess. And at

night, I opened my laptop and went to work again, messaging students and

grading their essays. The pain of their ruptured lives was weighing on me, and

I absorbed that as well. I can handle this, I thought. I can do it.

When I went grocery shopping, I thoughtfully selected what each member of my family needed for the week while ignoring the fact that I also needed to eat. When I was hungry, I scraped together leftovers that I ate too fast over the sink, my son on my hip licking hummus off my finger while my daughter ate at the table. I took on a particular tone, at once bragging and complaining about the weight of my days. I saw myself edging toward a version of myself I didn’t like but didn’t know how to stop.

Eventually, something unlocked in me. That is the nice way of saying I

exploded.

*

I do have some memories of my mother not moving. She used to read E. B. White

books to me. I can feel her sitting next to me in my bed, watching her hand

hold down the yellowing pages.

*

When our daughter was two years old, I debated getting a job as a technical

writer. I had a phone interview. Then I made an appointment to tour a day care.

I carried Mae, following around a young woman who pointed out sensory bins,

learning centers, reading nooks, rows of blue cots where the children napped.

“Every week has a theme,” she said, pointing at a board. “This week it’s the

ocean.”

I nodded.

“We also teach Spanish,” she said and handed me a thick stack of paperwork to

fill out.

“Thank you,” I said.

When I placed my daughter in her car seat, I saw the white grip marks from my

hands appear on her legs and realized how hard I had been clutching her.

*

My conflict comes from this idea that I’m supposed to just enjoy being a mom.

I’m not supposed to covet a desk job in a newly renovated office space where

they do yoga in a warehouse. I’m supposed to receive my joy from watching my

children age imperceptibly, moment to moment. I am supposed to be okay with my

body, and not complain about the soft hill that is my abdomen, sliced apart by

two c-sections. I’m supposed to enjoy the fact that I have no retirement fund,

except the one from when I used to teach full time that is sitting somewhere,

untouched, a website I visit occasionally, a number I stare at. When I get a job

again, I am supposed to be okay with a lowered version of success. My mother

suggests becoming a substitute, and the metaphor is so heavy I can’t think of

anything to say in response. I am supposed to be okay with this because I made

the decision to be a mother, and mothers put their children first.

When I bemoan this issue to my husband, he wraps his arms around me. “Don’t

they know you are the brains of this operation,” he whispers, his chin resting

on my scalp.

*

The task of raising children seems impossible, the stakes far too high. I

can’t believe how other parents appear to know what they’re doing. Sometimes,

pushing my children in a cart through the grocery store, I want to scream,

“What the fuck am I doing? What is happening? Is this right? How did we get

here?”

My breakdown happened slowly, over the course of years, and it started that

early summer afternoon, crying with my student. That agony of motherhood,

unmistakable in its breadth, hooked me to her, just for a second, and I cried

for every mother that had to wonder if their children were safe. Later, when I

had a son and he was a cooing lump in his bouncer seat, my daughter running in

circles around him, I would stare at them and think, How on earth are we

going to fill our days?

“Stay home,” I said to my husband one morning after his alarm went off,

knowing that he couldn’t. I was desperate for him, and I felt bad for putting

that on him, but I was in a dark space, my patience gone, unable to deal with

the whining, the diapers, the vaccination schedule, the stares when I gave each

of my kids an iPad and we sat in a Starbucks so I could drink coffee for five

minutes in silence. Weeks later, when I asked him to stay home again, he

apologized for not taking the day off in the first place. “I should have heard

what was in your voice,” he said.

Sometimes, befuddled by the depth of my loneliness, I wept alone in my

bathroom while my children ate at the table. I knew it wasn’t right, but when

you are in it, you don’t know you are.

I didn’t want to say I had it. No, I thought, dumbly, urgently, not me.

At the pediatrician’s office for my son’s appointments his first year, I had to fill out quizzes asking me safe little questions like, When something goes wrong, do you blame yourself? Are you able to laugh at jokes?

This is a joke, I thought, and filled out the answers the way they were supposed to be done. Neat, clean, positive.

Everything’s super!

At times, I could force myself to remember myself. I had a mind. There was a

child in me: my mother’s child. She was also someone’s child, but she grew up

in a time where women weren’t allowed to run the full court during a basketball

game. It made her mad.

It makes me mad.

*

Over New Year’s my husband came into the kitchen and started massaging my

shoulders while I read the course textbook at our table. “You should take the

summer off,” he said, his voice above me, cautiously, because he knows I

don’t take well to advice. “Give yourself a break from teaching and go back in

the fall.”

It was a typical northeast Ohio winter, and I stared at the gray skies that

had always comforted me and said something along the lines of, “I’ll think

about it,” though on the inside I was thinking no fucking way.

*

A message from my undergraduate creative writing professor: “Would you like

to come back and give a reading?”

Yes.

Please.

Save me.

*

One day a friend stood in the door to my office and we talked about what it

was like to have babies. Mae was only 6 months old, and I thought we were being

honest with each other, talking about how wild it is, to stare at our children

and feel a raw kind of love we knew nothing about.

“Yeah, it’s crazy,” I said. “It’s also really hard.”

Her face flickered, and I knew immediately I had said something wrong. It was

the first time I realized we were not supposed to say things like this.

*

Mae discovers the camera feature on her iPad and starts roaming our house,

slowly, the iPad held out in front of her. I notice her standing quietly in a

corner, or sitting on the arm of a couch, and don’t think much of it. She

delights in her burgeoning film career, occasionally showing me the pictures

she takes of candy wrappers or Wilder’s gaping mouth.

“That’s wonderful,” I tell her, glad that she has something vaguely artistic

to occupy herself with while I load the dishwasher.

Months later, dazed on the couch after everyone is asleep, I watch the

screensaver function come alive on our television. Todd has it set to play a

slideshow from our various devices, and I see a stream of pictures of myself.

There I am, walking up the stairs with a basket of laundry, phone clenched

between my ear and shoulder. There I am changing Wilder’s diaper. There I am

reaching under the couch for a motorized train. I see my stomach that I try to

stuff under high waisted yoga pants. I see the blue moons beneath my eyes and

fresh strands of gray hair. But there I am, also, feeding Wilder a piece of

watermelon in a blazing strip of sunlight on the kitchen floor. I am sitting

with my back against the dishwasher and Wilder is standing in front of me, his

hand on my knee. I am smiling at Wilder, who’s smiling at the camera. He has

juice on his chin, and his smile is simple and toothless. I am smiling so

deeply my face is contorted. I could have been screaming. Here he is, still my

baby, and I have him. In the photos, you cannot see that I am doing anything

extraordinary, that I never left my children. You don’t know that I still see

them at the top of every page I write and search for them every night in the

forest of my dreams.

*

A few days after my weepy email to my boss, I got a response. I sensed a

kindness in the language. “Dear Megan,” she wrote. “I want to assure you that

you did nothing wrong.” I relaxed, but then I felt a wave of guilt for pinning

such an emotional email on her to answer in the first place.

Her email was longer than it needed to be, and my guilt deepened. “By the time

you got back to me saying what you wanted to teach, there were no more sections

available,” she wrote.

I went back and sorted through my email. I saw that I waited nearly two weeks

to request one section for the summer. My body knew before I did that I was

doing too much.

If I wanted to move beyond postpartum depression, I had to accept that I had

it, which is something that I am still doing. I had to decide what kind of

mother I wanted to be. One day, walking into the living room, a thought came to

me: All of your problems are created by you. If I let myself relax, if I

forgave myself — for what? Trying to be good? — everything seemed to unclench.

In our new world of empowered self-care, we teach women to ask for help, that

there is nothing wrong with calling your friends and saying you’re tired, you

need help. In this same world, though, we also tell women that it’s okay to put

themselves first, value their time, say no. We don’t like to think of it this

way, but couldn’t that mean one mom telling another that she’s sorry, but she

can’t help? I had to learn to demand, not just ask for, help. And when someone

told me no, I can’t, I had to let them, because that is what I wanted people to

do for me.

*

On the occasional Tuesday night, my husband shoves me out the door and tells

me to go somewhere. Usually I drive to a coffee shop, retreat to a corner, and

write for three hours without standing up. But one night I decide just to sit

at a bar, drinking the house red and doing a crossword.

Bring home pizza, my husband texts.

I’ve had two glasses of wine by the time I float over to Lorenzo’s. I feel warm and thoughtful, drifting in and out of my own analysis of a dream I had last night.

“Didn’t we go to high school together?”

I look at the man in the window of the pizza shop.

“Matt Kokowski,” he says.

I keep looking at him, his shaved eyebrows, dyed hair, so many tattoos they seep out his shirt collar and up his neck. The expression on my face was the same one I must have when I sit and meet with my tax preparer.

“That is who you are,” I say, my tone shifting word to word, not quite a statement, not quite a question, as if, perhaps, we are beginning a conversation where we just announce the full names of people we know.

He turns to get my pizza, leaving me in my wonderment.

“I think we rode the same bus,” he calls back.

“You look different,” I offer.

“Well, it’s been 20 years,” he says, setting my pizza on the counter between

us.

I sign the receipt and leave him two dollars in place of my usual one for the

person who hands me the box. I remember Matt Kokowski, but he was a child when

I knew him, and so was I.

*

Let’s just pretend Another College, up the road from me in the other direction, offers me a job. Full time. Some dreamy class load of 2/2. Upper level poetry and creative writing. I would imagine my office. I wouldn’t turn on the overhead light but instead keep a lone lamp on my desk so I could work under its circle of light, something I recall from my thesis advisor’s office, which always felt soft and right. I’d have a sweater over my chair, framed black and white pictures of my children on the wall.

My children. My son, who isn’t even in preschool yet. My daughter, who will be in kindergarten next year. I relish the light of their innocence, their newness. She still loves nursery rhymes, and we sing them together in the car. He just learned how to say excavator, cottage cheese, and tortilla. One of their favorite games is to hold hands and run together in the backyard.

I wouldn’t take the job. I know that now. I don’t need that to save me.

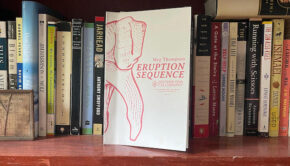

Photo by Patrick Selin on Unsplash