GRIEF STRUCK: An Interview with TOM HART on ROSALIE LIGHTNING

Tom Hart and Leela Corman’s daughter Rosalie Lightning died, suddenly and unexpectedly, before her second birthday. Their tragedy shocked the indie comics publishing community, particularly here in New York, where the couple had been fixtures as teaching artists. They had only recently relocated with their small family to Gainesville, Florida, on an adventure to found a cartooning school (SAW). They were starting fresh, when this grief struck.

My own daughter had just turned six months old, when theirs died. Like many new mothers, I was terrified by the vulnerability of the life born to me. Post-partum, I was raw and open. When I heard about Rosalie, I remember I began rocking on my bed, keening. Any child could be taken, overnight. These parents now lived in this unthinkable.

“Your family is in my thoughts,” is a thing you say. That has very much been true. I have thought of Tom and Leela almost every day since.

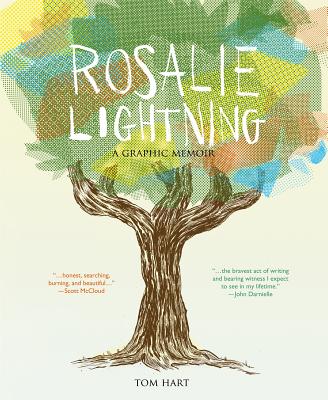

Tom Hart has now published a book about his daughter and her life, and her death, and the journey through the weeks after. Read this stunning excerpt posted at MUTHA. Rosalie Lightning, the book, is a memoir and a memorial. As John Darnielle says on the jacket, “If it’s hard to talk about Rosalie Lightning without sounding hyperbolic, it’s only because its achievement is so breathtaking: the bravest act of writing and bearing witness I expect to see in my lifetime.”

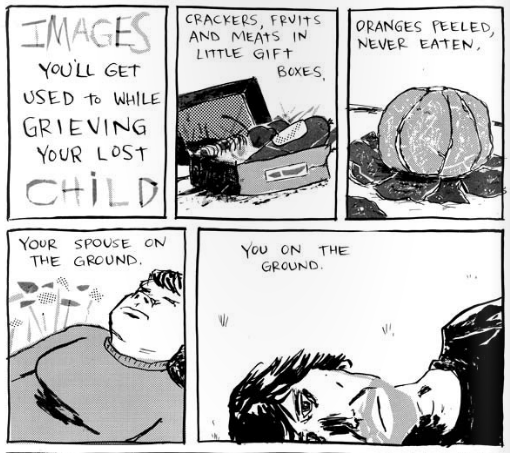

I could read Rosalie Lightning only a few pages at a time, sitting in the corner seat of the cafe where I often work, hiding my face. (Though as it’s often said of New York, here you can openly weep in public, without much fear of being disrupted by the human sitting next to you). I found myself bodily undone, affected with a fevered sadness, which reminded me of years back when I read Cheryl Strayed’s gorgeous first novel, Torch (based losing her mother; and now I was a mother, and the worst thing I could imagine had shifted to losing my child). When I brought Rosalie back home, my daughter said “I want you to stop reading that sad book!” She tried to take it away. But, I told her, sometimes sad stories are the most important ones to recognize in the world, the truest. As a parent, this grief feels unimaginable. Tom Hart’s artwork and storytelling precisely immerses you in what the mind doesn’t want to approach, and somehow also brings light into that darkness, beauty.

I called Tom by Skype for this interview, and he sketched as we chatted. I’m grateful to him for his patience, first when our connection went buzzy and we had to restart the call and tape, then later when I lost it, choking up in the middle of the interview. He is a calming presence, a nice quality in an educator. Thanks, Tom, for taking the time to talk to me about comics, this book, and your child.

And now, I hope everyone will read this sad book. Be brave and be amazed by it, with respect to the terrible unfairness that it exists instead of the little girl who was named before it, lightning through the darkness, an image echoing when we close our eyes. – Meg Lemke

MUTHA: I’m sorry about having to re-start the tape. This is hard enough to talk about already.

When did you start writing Rosalie Lightning? I’m assuming you started Daddy Lightning soon after she, your first daughter, was born? So, did you ever stop writing about her, her life, and after?

TOM HART: I began Daddy Lightning after Rosalie’s first two or three weeks of life. But while I wrote some pages and took notes, I was mostly too overwhelmed in her infancy to complete it. I finished it after she died.

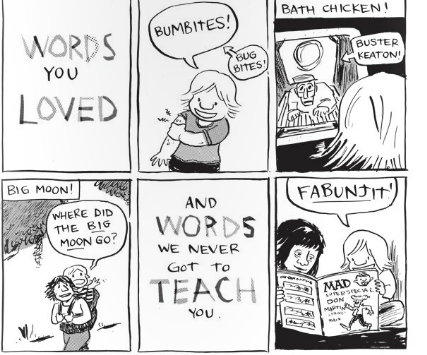

But the stories I started after she died, which became Rosalie Lightning, I started writing instantly. I’ve always made books of what I’ve experienced. I’ve used comics as a way to negotiate the world—the external but also internal, emotional world. From my earliest days when I was a child, of 6 or 7, I was tracing Peanuts characters. Comics portray such a range of feeling, drawing has helped me identify or manage emotional states.

I realized recently that anger, confusion, and exuberance have been the three threads running through all of the work I’ve done, from my earliest mini-comics to this book about Rosalie.

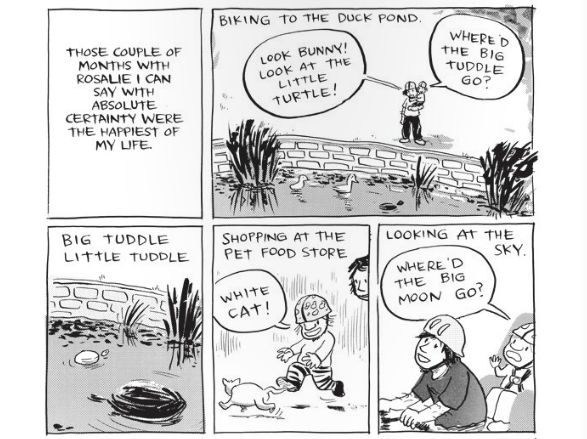

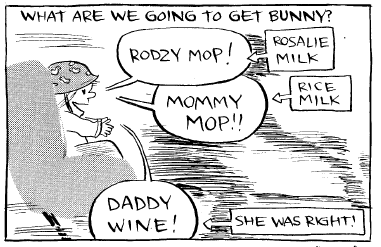

Rosalie provides the exuberance in her story.

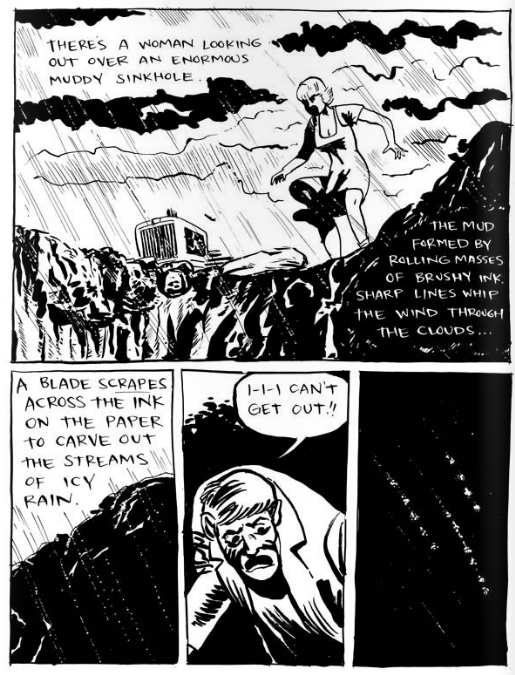

MUTHA: This is a very loving book. It’s interesting to think about how it also comes from anger. There is an affecting scene, where you are speaking to a therapist who suggests you could externalize your anger with the cliché of hitting a pillow—as if you could go out and break such a mountain down. You show yourself drawing and un-drawing a mountain down, breaking down the emotions on the page, instead.

TOM HART: Drawing is very physical. I’m trying to understand, more and more, as I get older, what degree it’s an artifact of our physicality. In creating this book I was drawn to more physical acts, like how I used shading film, which involves carving into stickers. It’s not chopping wood, of course. But it’s drawing with a knife. I also used the brush often, and a pen that would scrape the page. The brush had a soft, mushy sound. I’ve never used a brush as much as I did in this book.

There was also the act of trying to recreate what I’d been through, to take reference photos. I took a lot of photos. Even silly things like walking. I’d get up out of my chair, put my feet in position to walk. It should be an easy thing to draw, but the act of getting into those positions was important. The book was like trying to relive those first five weeks in this long period of time. All of it was an attempt to experience it somehow deeply and correctly.

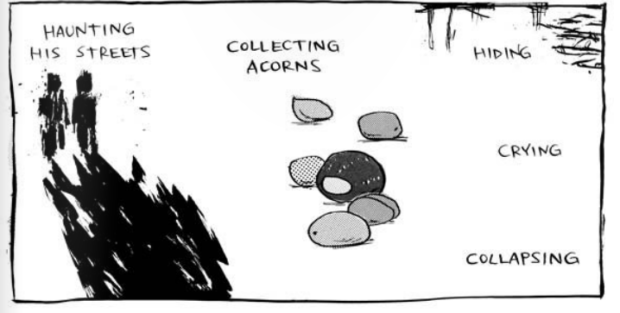

When you experience something like this, it would have been easy to become self-destructive or numb. I wanted to let it be a part of me, not to deny it.

MUTHA: Alison Bechdel often describes taking reference photos of herself, as well; I’ve heard that discussed more as a technical curiosity, but as you’re describing it, it sounds powerfully therapeutic. There are movements in therapy where you place yourself in a tableau, to activate and process memory.

TOM HART: Incorporating this huge binder full of notes I took, into a narrative structure full of drawings, it took almost twice as long as Rosalie was alive. That was all part of an integration process, trying to make myself into an emotional, physical, intellectual being, coordinating those parts into someone who could move forward and have this experience behind him.

MUTHA: You pause in one panel, in a scene early in the story, and write “I want everyone to mention Rosalie.” As a reader, I felt this gave a moment of reprieve. This book is hard to read, and some people—parents in particular—might be afraid to talk to you about it. Afraid even to read about it. To acknowledge this grief, which cannot be denied.

“I want everyone to mention Rosalie” is almost a purpose statement for this beautiful book. It invites conversation, and it brings an understanding of her and her life to people who never knew you before. Is that why you wrote it?

“There’s no such thing as non sequitor when you’re in love” – Ben Lerner, epigraph to Rosalie Lightning

TOM HART: When I started writing it, I wanted to keep her spirit alive. I was trying to share what was so vibrant and vivacious about her. One thing I asked people, when they would email us, right after she died, was for a story they remembered. It was nice to hear little things that she had said or memories of when she played with friends’ children. The insights of others about her were inspiring.

I liked to hear these stories, because that was all that was left of her.

A couple people sent videos and that was the absolute worst thing. I shoved them in a corner or deleted the files.

It is hard to know what a parent will want. I did want to talk about her, a lot. And I probably didn’t, also.

MUTHA: Now that the book is published, is it still something you want?

TOM HART: I don’t know. Here in Gainesville, I did a reading a few nights ago. A woman came up to me—actually she was brought up, by her friend, and the friend said “this woman’s in your book.” Come to find out, she’s the woman who owns the chicken. “That’s my chicken!” she said. In one panel, a small moment, I mention Rosalie and I meet a chicken, and the owner says the chicken leaves its own coop to escape the raccoons every night. I was really happy that the woman came to the reading, so happy to talk to her. That was a rare instance of finding more of Rosalie’s story out there, details I didn’t know yet. That won’t happen much more often, I think.

MUTHA: But now, people who didn’t know Rosalie before are reading the book and meeting her there. So the stories they are going to tell you are their own stories. Or, their interpretations of her and her life. And maybe asking you questions you don’t want to be asked?

The act of this book invites the conversation with you and your family about this loss. Is there a right or wrong way to speak to someone about their grief?

I have to tell you. I wrote you a number of emails over the years that I didn’t send. Out of fear of interrupting, not knowing if it was the right time or thing to say.

TOM HART: What do you say? I don’t know. What helped in my case might not have helped someone else, or might not have helped in a different moment. You are bouncing back and forth in emotional state. Someone bought a copy at a recent reading, for their son who had just lost a child. And all I could say was, “Oh, dear.” It sounded like a horrible thing to have happened. I didn’t know what to offer. And that was at the remove of a grandparent.

It wasn’t my intention to open a dialogue about how to cope, but rather I wrote the book to cope myself. I wrote the book to keep her alive and stay connected to her. I am probably not the right person to talk to about how anyone should deal with grief.

MUTHA: Why do you say that? Because you’re not a therapist, or an “expert”?

TOM HART: Well, I’ve got an open heart. But, I’m not verbally expressive. But I don’t know if in real space I have the skills, enough to offer other than an open ear and heart. I’m happy if people have gotten anything out of my book. I’m really happy if it helps in some way.

I’ve answered many emails, and just discovered a hidden Facebook folder with messages that I’m answering now. Some are so sad. I’m trying to be fully present as I answer them. I don’t know anything about the subject of grieving, but what I went through, and yes, if I can help people, I want to do that.

MUTHA: You use literary inspirations as touchstones throughout the narrative of the book. How did these come to you?

TOM HART: When we were at our most desperate, I was looking for signs that we weren’t so alone. I wanted to see my emotional self reflected. I collected stories—it helped to know that other people had experienced loss of any kind. When a brother had lost a brother, a friend who lost a sister.

We also saw our story reflected everywhere, where you would not expect. To show you how random that could be, here’s a story I edited out of the book. One of the first movies I tried to watch, to try and keep my mind off things, was Klaus Kinski’s biography that he wrote and directed about Paganini, the violinist. I thought, how long can I get into this before I’m miserable and reminded that my daughter is gone? It seemed utterly unlikely. Then, almost the first scene has Kinski as Paganini, ridiculously cocky, walking—and the people, especially the women, are screaming with pleasure. It’s like the Beatles. That instance reminded me so concretely of Rosalie. If I came home after being out all day, she’d give this big scream. Leela called it “Dad Beatles.”

Ten minutes into this Kinski film, I had to shut it off.

As I tuned my brain, and filtered out what didn’t help, I found the stories that I needed. The Kurosawa movie I write about in the book, “The Men Who Tread on the Tiger’s Tail,” which had nothing to do with the loss I was experiencing, it was a very rich experience—it was about a sorrow, about trying to maintain something difficult to maintain. All the parts that spoke to those themes were amped up, went deep into my brain.

Everything mattered on this journey I thought I was on. It reminded me of when I was young. If you’re very young and you believe you are on some sort of path, you tune your eye to it and you see images of it everywhere. There’s a similar openness you experience: when you’re very young and the world is in front of you; or when you are in love, like Ben Lerner says in the epigraph to the book; or when you are deeply in pain. There’s an openness, an attentiveness, it’s easier to maintain for a while. If you let it, it helps you take that next step.

MUTHA: I felt that powerfully, through the medium of comics. You immerse the reader in the shifting visual poetics of the world. There’s a kind of hallucinatory experience in the grief you’re going through. Some writers achieve this in prose, for example with an unreliable narrator—but you have created an unreliable landscape in the comic. You play tricks on the reader. It becomes an accurate representation of the inaccuracy of the world around you in grief.

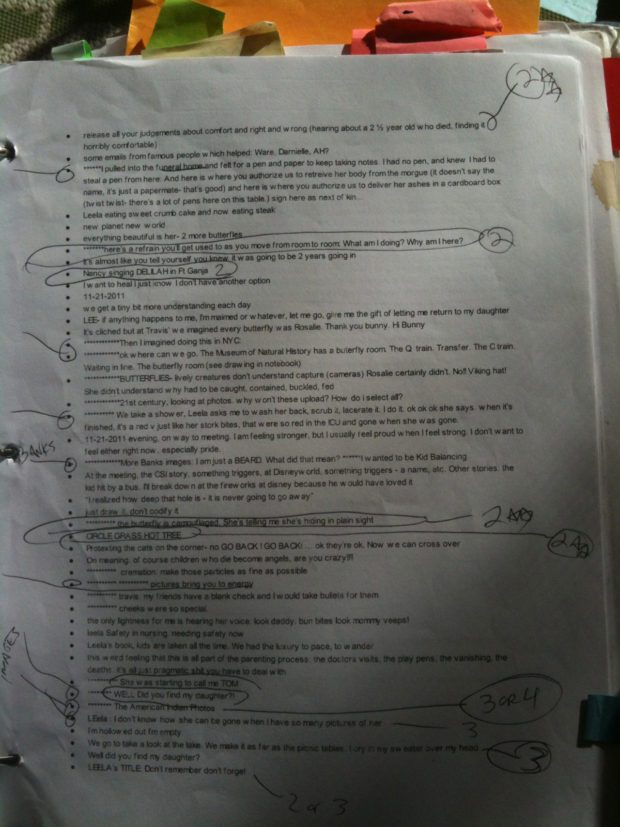

TOM HART: What I was perceiving changed and was all over the place—I was taking notes about that as it happened. Here’s that binder, full of notes. I was trying to document all that I was experiencing, internally and externally.

MUTHA: How did you then edit it all down? There are production choices that caught my attention—you have chapter break pages that are black, and a whole section that’s black background, white on black. If you hold up the book, you can literally see in the closed pages the period after Rosalie dies, it’s dyed into the physical structure of the book.

TOM HART: Yes, it’s right there.

MUTHA: But look how much light there is, as well.

TOM HART: That’s a nice way to phrase it. That structure wasn’t intentional early on, but it was intentional when I got there. When I first started drawing, I told myself I’d use a nine-panel grid and not think about it anymore. But when it came time to draw that worst period, it didn’t make any sense. I left the grid and I just drew every moment separately. I needed to draw it as if you were peering from some abyss through these dark holes. It’s how I had experienced that time—one moment and then another, utterly isolated from others. Fragmented.

Then what emerged, in the next chapter, was a simpler grid, as if it was trying to get back to the nine-panel grid but couldn’t. From the worst, you begin moving forward.

MUTHA: You also chose not to draw some scenes.

TOM HART: Early on, I thought I would need to share the whole story—because it was so horrible—all the details, including the grimmest ones. When it came time to think about how to draft some of those moments, I didn’t want to draw it. No sane person would want to read it. That realization was helpful. I realized the book needed to pivot a little and I needed to use it to get myself out of those holes.

MUTHA: Out of reliving the scenes you didn’t want to draw?

TOM HART: The worst of it was in the hospital, the day she died. I created 3 or 4 panels that were illegible. Early on, there might have been a slightly sadistic streak telling this story. I didn’t want to be the only one in pain.

As I mentioned, my work hits three themes—anger, confusion, and exuberance. But truth be told, there’s not a lot of anger in this book left over. That’s what I started out with: anger. But it wasn’t helpful. I realized that the part of me that wanted to tell the entire story, show all the darkness that we went through, it might have been the anger talking. I realized it needed to be a healing book. I kept in the parts that helped that happen, and the worst of it I kept out.

MUTHA: Your wife, Leela Corman, is also a cartoonist. What was it like to draw the book, next to her? You’ve written in blog posts from that time that Leela wasn’t ready to start drawing about it herself, though she later took the topic on in a different way.

I have to say: You have such an inspiring, beautiful marriage, portrayed in this book…

[I started crying here, audibly on the tape, and step away on the Brooklyn side of this conversation to “get the plug to my laptop.” There is a long silence, the recording hissing, and the sound of Tom also moving in his room in Gainesville.]

I’m sorry, Tom, I thought I could keep it together. Have I lost you?

TOM HART: I’m here. I went to get some water.

MUTHA: How did you make it through? It’s a truism that many marriages do not survive this grief. You seem to have made a conscious choice, meditating and turning to each other and repeating: Solidarity.

TOM HART: We get along pretty well, I guess. We’ve been together so long. Twelve years before we even had Rosalie. Luckily, neither of us has a tendency to give into darkness. We’re both motivated by beauty and life—however horrible it is. We both have a realistic view of the injustice in the world and the ugliness everywhere, but we feel motivated to improve things, or at least express ourselves in some positive way when we’re down here on this planet.

One small thing that utterly changed, soon after it happened, we noticed our way of behaving together in space had completely reversed. She sat still a lot; she’s usually very active. I moved around a lot, when I usually like to sit, read or draw.

I was wondering if Leela would draw anything or write anything—she spent a long time zoned out, longer than I did, over a year. I was forced to engage; I was starting SAW, my school, at that time. The events of this book end around January 1st; the school was up and running by January 12th. It was pretty bare bones—mostly a room and a table. But I spent a lot of time in that room; I’m in that room now. I spent time painting the walls, painting the floor. All the while thinking about what I was going to make about Rosalie. Writing and drawing motivates me, it’s always been the thing I’m most interested in.

Leela, when she finally did start writing and drawing about grief, did it in a profoundly different way. She’s not done. She’s taking notes and hers are broader than mine. My writing is raw and insular, about my experience; she’s tying hers into larger themes. She’s looking at intergenerational resonances; her grandparents were Holocaust survivors, her rich experiences growing up in New York.

As the counselor says to Leela, in the book: your generation has the luxury to grieve. There is a truth that it’s going to be her role for a while, now, to portray that—all the stuff she has in the hopper is tinged with grief, whether its fiction or essays or illustration jobs. It will serve the world as she releases that art.

MUTHA: You have a second daughter, now. How do you imagine her relationship to the book?

TOM HART: I’m less interested in the relationship to the book than I am in her relationship to her sister. I don’t know how that will develop. We talk about Rosalie now more than ever, because Molly Rose is at the age that Rosalie was—she’s a little older, but her sense of humor is now coming out. Her assertiveness is coming out, her language has just surpassed Rosalie’s. Molly Rose hears everything we’re saying, I’m sure.

MUTHA: Oh, they do! I know—and I have a very hard time around my daughter, not to wear my heart on my sleeve.

TOM HART: We don’t really know how we should be careful.

MUTHA: Has Molly Rose asked you who Rosalie is?

TOM HART: No, she’s still too young. She’s like “Stop!” “Give me that!” “I want to follow you to the bathroom!”

MUTHA: She spilled the ink over the table at the New York book signing…. That was funny.

TOM HART: No that was me! I was tired.

MUTHA: There’s a note at the end of book where you acknowledge people who have lost children, particularly to war or violence. This is a moment in history, but really it’s all of known human history, where children are being lost to violence. Were you more attuned to that while writing this story?

TOM HART: The news was so full of horrible situations, of black children dying, Syrian children dying, so many great injustices. I felt many times privileged to be telling this story, and not some other story. We’re lucky.

I don’t know if I was more alert to the violence, or if the violence just kept happening. Children are dying all the time, children are losing their parents, parents are losing their children—it’s constant. I’ve always had too much empathy for crises in the world but never enough knowledge about how to help. I’m still not sure; I am thinking a lot more and feeling more deeply but I don’t know what it means. I wanted only to acknowledge that there are people in worse situations than those in this book.

I wish I could tell the world, this pain that Eric Garner’s family feels, that other people’s family feels, is not going to go away in a year or two years. There’s a person there, hurting. Utterly wronged. Not just the dead person, but the living. And, I felt like I was lucky, like I wasn’t wronged. Usually I’m full of rage at the social structure—I don’t think I would have been able to write this book if my situation had been different. For Rosalie’s death, there are no people to blame, there’s no social structure to blame.

MUTHA: I hear you, but I wonder if there’s also a particular hardship to not knowing what happened to your child.

TOM HART: I struggle always to have one eye on the unknowable. There are always questions we won’t have answer to—why we’re here, being the main one. Making this book was my attempt to put this question of her loss into that abstract category, and to become at peace with it, just as I know I will not get any closer to the unknowable of why any of us are here.

MUTHA: It becomes a philosophical book.

TOM HART: I wanted to push it in to that category. Leela and I, in our solidarity, we understood we would need to find manifestations of Rosalie elsewhere, to remember her, to see her in beautiful things. We understood that early on, but I at least needed the years of making this book to put those understandings deeper into my body and my being.

“What catapults this graphic novel into greatness is its honesty… Rosalie Lightning is a masterpiece—and a luminous tribute to a brief, beautiful life.” – Publisher’s Weekly. Recently, Rosalie Lightning was chosen as a Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writer’s pick (the only comic on the spring list!). Get it, read it—and share your thoughts in the comments.

2 Responses to GRIEF STRUCK: An Interview with TOM HART on ROSALIE LIGHTNING